|

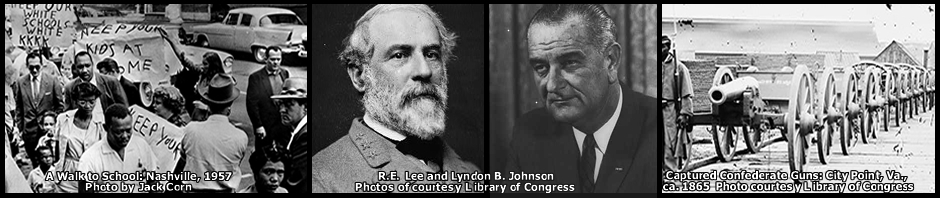

1864 It was getting late in the war, and both sides knew it. What they didn’t know yet was who would win. An exhausted North could sue for a negotiated peace and allow the continued existence of the Confederacy, or a decimated South could lose both its self-conferred national identity and the 240-year-old slave-based labor system that had produced its vast wealth. Each side got more desperate in August. In Virginia, Union Lt. Gen. U. S. Grant fidgeted at Petersburg, Richmond’s back door, trying to trap and bag Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army. In Georgia, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman closed his grip on Atlanta. On the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, the North’s three-year naval blockade was now choking virtually all international commerce out of Dixie. On Aug. 23, Mobile fell, leaving Wilmington, N.C., as the South’s sole major operating port. So the now 41-month conflict had devolved into a single question: Could the South keep the war going strongly enough for Northern Democrats to achieve a November defeat of the re-election bid of President Abraham Lincoln, who was determined to push the war to a Southern surrender? If not, it would soon be all over. * In Washington the Radicals, whose Wade-Davis Bill had claimed for Congress the authority to set rules by which seceded states might re-enter the Union, blasted the President for pocket-vetoing their measure in July. The so-called Wade-Davis Manifesto, issued on Aug. 5, described Lincoln’s rejection of their position as “grave Executive usurpation” and asserted that “the authority of Congress is paramount and must be respected.” If Lincoln wished their support, it said, he “must confine himself to his executive duties–to obey and execute, not make, the laws.” Lincoln, though, by this time had little choice but to ignore Congress. He already had fledgling loyal administrations in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas trying to steer their states back into the Union. The Wade-Davis Bill had tried to change the rules the President had set up for doing that. The Radicals wanted to make the process much tougher, if not impossible in the foreseeable future. Under their plan, a state must first completely abolish slavery. It must also institute elections in which 50 percent–not the Lincoln-mandated 10 percent–of the state’s population had to be eligible to vote. And the seceded state must require that electors of its constitutional conventions (whose first jobs would be the abolition of slavery and setting up new government) had to take an oath of past allegiance to the Union, not just the future allegiance that Lincoln had demanded. This meant that no resident who had ever supported the Confederacy could vote. As always, the devil of politics lurked in the details. The Radicals were all Republicans, members of Lincoln’s own party, but they had never loved Lincoln’s tendencies toward moderation, and most of them had come to like him less and less. They were afraid he would abandon emancipation in the interest of restoring the Union, and many now also feared that the little 10-percent pockets of Unionism he had gathered in Tennessee, Louisiana, and Arkansas might provide the votes he needed to squeak through to a second presidential term. One Radical, probably the most radical of them all, refused to support the Wade-Davis Bill. In mid-August, brilliant and dangerous U. S. Sen. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania let it be known that he no longer supported not just Wade-Davis but also Lincoln. Stevens, an implacable enemy of slavery, spurned Wade-Davis because it was not tough enough. He still believed exactly as he had said of the Confederates in a speech on the floor of Congress in 1862: “I would seize every foot of land and every dollar of their property as our armies go along, and put it to the uses of the war and to the pay of our debts. I would plant the South with a military colony if I could not make them submit otherwise. I would sell their lands to the soldiers of independence; would send those soldiers there with arms in their hands to occupy the heritage of traitors and build up there a land of free men and of freedom, which, fifty years hence, would swarm with its hundreds of millions without a slave upon its soil.” The Kentucky-born Lincoln was far too much of a political compromiser, and maybe also too much of a Southerner, to hold such harsh views of the South, but he knew he needed the Radicals. Without them, he never could have gotten Congress to pass Emancipation. He knew something else, too. “They are nearer to me than the other side, in thought and sentiment, though bitterly hostile personally,” he had told his private secretary, John Hay, in 1863. “They are utterly lawless, the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with, but, after all, their faces are set Zionwards.” In other words, in Lincoln’s view the Radicals were on the side of the angels–in an America where Satans of racism ran rampant. * In the Eastern military theater, Grant prepared to starve out Lee’s bottled-up troops around Richmond. On Aug. 1, he ordered cavalry chief Philip Sheridan to clear the Shenandoah Valley of enemy troops, especially those of troublesome Confederate Maj. Gen. Jubal Early, and destroy the Valley’s potential for supplying food and forage for Lee’s army. Some of Sheridan’s troops defeated part of Early’s cavalry at Moorefield, W. Va., on Aug. 7 and captured Early’s cavalry commander, John McCausland, along with 420 other Confederates. Sheridan on Aug. 12 went after Early himself, who was dug in around Cedar Creek south of Winchester, Va. After two days of skirmishing, though, Sheridan needed supplies and withdrew toward Winchester. Early pursued, and the two fought on Aug. 17. In their first aggressive action since the Crater explosion of Confederate lines at the end of July, Grant’s troops at Petersburg on Aug. 18 grabbed more than a mile of the Weldon Railroad leading south out of the city. On the 19th, Confederate Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill attacked the Federals and pushed them backward, but not far enough to recover the lost stretch of rails. Hill tried again on the 21st, to no avail. He lost 1,600 of his 14,000 men trying to regain it, while the Federals lost 4,425 of 20,000 holding onto it. Hill made a final attempt on Aug. 25 and cost the Federals 2,700 more casualties, but the Union hung on. Meanwhile, Early had pushed Sheridan across the Potomac. Leaving a force to hold him there on the 25th, the Confederate general again turned to thoughts of threatening Pennsylvania and Maryland. But he had no sooner left than Sheridan came after him again. * In the West, Sherman maintained his siege of Atlanta and dispatched from Memphis, 400 miles northwest, another Federal force to try to keep the Confederate he most feared, cavalry titan Nathan Bedford Forrest, off his supply line. Sherman ordered Maj. Gen. A. J. Smith, who had defeated Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee and Forrest at Tupelo in July, back into Mississippi against Forrest. Complaining over Smith’s rapid retreat from Tupelo after the victory, Sherman demanded that Smith “pursue and keep after Forrest all the time.” On Aug. 3, Smith left Memphis with more than 20,000 troops and headed for Oxford, Miss. Forrest was no longer encumbered by Lee, his commander at Tupelo, but he had just 5,000 men to defend the vital grain fields of the Mississippi prairie. With little or no alternative except unthinkable idleness, Forrest slipped past Smith and made a lightning raid on Aug. 21 into the city Smith had just left–Memphis–to try to force another Federal retreat. With him Forrest had just 2,000 men, having left the balance at Oxford to try to oppose Smith. Hoping to capture three Federal generals stationed at Memphis and liberate Confederate prisoners held there, Forrest was unsuccessful at either. He did, however, capture some 600 Federal soldiers and sympathizers and prompted one of the wittier quotes of the war. Maj. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut, who had recently been superseded by Maj. Gen. C. C. Washburn, referred to Washburn’s frantic flight from his quarters in nightclothes when he said: “They removed me from command because I couldn’t keep Forrest out of West Tennessee, and now Washburn can’t keep him out of his own bedroom.” Washburn truly had been unable to keep Forrest–or at least Forrest’s brother Jesse, a Confederate lieutenant colonel–out of his bedroom, and Smith fell back northward after burning Oxford. But Sherman had again kept the cavalry “devil” off his supply line. In Sherman’s front, on Aug. 10 Confederate commander John Bell Hood sent his cavalry chief, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, on a raid against Sherman’s rail line north of Atlanta, hoping to deprive the Federals of needed supplies. Unfortunately for Hood, Sherman already had accumulated enough supplies in late July, so by detaching Wheeler, Hood only deprived his army of its cavalry “eyes.” On Aug. 27, Sherman took two corps out of their trenches to move south to cut Hood’s last rail lines southward. Unlike previous Sherman attempts, this one would succeed. On Aug. 31 Hood desperately and disastrously attacked a Sherman subordinate, Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard, losing 1,725 Confederate casualties to Howard’s 170. For the Confederacy, Atlanta was all but gone. * Opposition to Lincoln teemed among Radical Republicans for most of the summer. Back in May, a rump convention of them in Cleveland had even nominated antislavery stalwart John C. Fremont for president in his stead. The carping and cursing kept up until Aug. 31, the day that so-called Peace Democrats meeting in Chicago nominated former Union general-in-chief George B. McClellan, a well-known friend of slavery who possessed politically formidable military credentials. Suddenly the Radicals realized they faced a threat worse than Lincoln. As U.S. Sen. Charles Sumner of Massachusetts privately wrote, “Lincoln’s election would be a disaster, but McClellan’s damnation.” Gruff old Sen. Thaddeus Stevens realized the same thing. He immediately urged German-Americans supporting Fremont to abandon Fremont for Lincoln. [For more, see The Civil War Almanac by John S. Boatman, Bison Books 1982; Lincoln by David Herbert Donald, Simon & Schuster 1995; Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South by Fawn M. Brodie, Norton Library 1966; The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry by John Watson Morton, Methodist Publishing House 1909; The Campaigns of Lt. Gen. N. B. Forrest and of Forrest’s Cavalry by Thomas Jordan and J. P. Pryor, Morningside Press reissue 1977; ‘First With the Most’ Forrest by Robert S. Henry, Bobbs-Merrill 1944; and The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001.] |

1964 And then, at the worst time for everybody except advocates for suffering African Americans, the three missing civil rights workers turned up dead. By Aug. 1 rumors had been flying, not just in Washington political and law-enforcement circles but also among the general population of Neshoba County, Miss. The Mississippi talk had it that the FBI was offering eye-popping sums of money for information that the county’s large cadre of Klansmen doubtless possessed. Everybody knew it would take just one greedy renegade to disclose the grisly secret behind the KKK’s oft-voiced, disingenuous speculation that the missing trio had “gone to Cuba.” By the onset of August, the FBI too knew the secret. It was itself spreading the high-dollar rumors to protect a local informant who already had accepted $30,000 to tell the location of the bodies. Under pressure from President Lyndon Johnson, who in turn was under enormous national political pressure, the Bureau’s small army of Mississippi investigators considered the price of the information “cheap,” to use the word of one. “We’d have paid anything,” he said. No wonder. The search was massive. It involved 258 agents who interviewed more than 1,000 Mississippians. In an operation with a total cost approaching $1 million, $30,000 was indeed inexpensive. Nearly half of the Mississippians interviewed, 480 of them, were Klansmen–“just to show them we know who they are,” reported Bureau Director J. Edgar Hoover, whose extreme political conservatism made him accept this assignment with repugnance. He surely knew that many of his, and his agents’, friends in Dixie law enforcement were Klansmen. On Aug. 4, agents took a Caterpillar bulldozer with a 10-foot blade to a recently constructed pond dam on the property of Neshoba farmer Olen Burrage. They dug for six hours in 106-degree heat and knew they were getting close when clouds of flies and flocks of vultures gathered. They then abandoned the bulldozer, and, 14 feet deep in the dam, started digging by hand with garden tools, some smoking cigars to try to dilute the increasing stench. Two hours later, they unearthed the first body, shirtless and face-down in the dirt. The left rear pocket of the corpse’s pants contained a billfold belonging to New Yorker Michael (Mickey) Schwerner, 24, a 1961 graduate of Cornell University who had volunteered to come South with his wife Rita after the Birmingham bombing that killed four African-American schoolgirls in 1963. He and Rita had summoned the courage to open a community center in Meridian for the Congress of Racial Equality in early 1964. To foil Mississippi lawmen eavesdropping on their calls, the FBI agents used a code to relay the news to Washington. “We’ve uncapped one well,” they reported. The other two “wells”–the bodies of Andrew Goodman and James Chaney–were soon similarly “uncapped.” The word hit the White House amid frenzied tension. President Johnson and his advisers were trying to sort out murky details of an alleged–and eventually adjudged phantom–military action between U.S. and North Vietnamese sailors in the Tonkin Gulf off the Vietnamese coast. Johnson, already running for election to his first full term as president against super-hawkish U. S. Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona, feared the electorate’s reaction “if we tucked our tails” and ignored provocation. The news from Mississippi was even less welcome than that from the Vietnamese coast. It arrived less than three weeks before the Democratic convention in Atlantic City, N. J., was expected to formally nominate Johnson. * The civil rights workers’ funerals occurred as the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party hopefully chose delegates to the impending Democratic convention. Particularly poignant was the fact that, despite the wishes of the trio of families, these three young men who had died together in Mississippi terror were forbidden by the state’s funeral-home segregation law to be buried together. Chaney, the trio’s black member, had to be taken home to Meridian for interment alone. The MFDP’s founding statewide convention in the Masonic Temple in Jackson, which opened on Aug. 6, rang with denunciations of the continual outrage that passed for racial justice in Mississippi. On Aug. 7 David Dennis of CORE, shaken by the sight of James Chaney’s crushed young brother Ben in the audience, lost control of what he had intended to be a pacifying speech. “I’ve got vengeance in my heart tonight, and I ask you to feel angry with me,” he shouted, in tears. “…The best way we can remember James Chaney is to demand our rights…If you go back home and sit down and take what these white men in Mississippi are doing to us…then God damn your souls!” Ninety miles east in Meridian, African American children and youths–delegates to a Freedom School convention–were ecstatic at the first opportunity of their lives to try to take the kind of action Dennis so shakenly called for. They drafted a declaration of intent to “break away from the customs which have made it very difficult for the Negro to get his God-given rights” in Mississippi and proposed 13 planks for the platform of the MFDP. On Sunday, Aug. 9, the New York funerals of Goodman and Schwerner drew overflow crowds and much news coverage of the savage price the Mississippi Klan exacted for violations of its de facto racial laws. Six days later, on Aug. 14, two of the most prominent African Americans on earth at the time–Hollywood actors Harry Belafonte and Sidney Poitier–experienced the price firsthand. Belafonte had recruited Poitier to accompany him on a mission to take a satchel full of $60,000 to movement leaders in Mississippi. “They might think twice about killing two big niggers,” Belafonte had joked. It was no joke, they found. Shortly after their private plane landed on a lonely landing strip outside Greenwood, their car was chased by a nocturnal caravan of Klansmen to an Elks Club hall. There, while they were greeted by an adoring African American crowd, bullets cracked the windshield of a car parked outside. At a farewell party for the stars the next day, a volunteer driver was shot in the head as he lounged outside beside his automobile. On Aug. 17, a week before the Democratic convention, the movement’s best-known leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., requested a meeting with President Johnson about the broadening crisis. White House aides set the meeting for two days later–then informed King they were adding other civil rights notables. King had had this kind of White House treatment before, from John F. Kennedy, who had padded a meeting so as to dilute the upshot. King changed his mind. He sent Johnson his regrets. * On Friday, Aug. 21, as buses carrying the MFDP’s would-be delegates were unloading in Atlantic City, Alabama Gov.–and wild-card presidential candidate–George Wallace decried Democratic leaders who were cottoning to such apostates. Wallace predicted that refusal to repeal the new civil rights law would foment an “uprising” like the revolt against Reconstruction in the South of the late 1860s and early to mid-1870s. The MFDP delegates, hoping to be certified by the national party as Mississippi’s rightful ones, came bringing evidence of the kind of oppression they had endured. It included a replica of the roasted steel husk of Michael Schwerner’s station wagon. One reason the MFDP went to Atlantic City early was to lobby regular Democratic delegates from such progressive states as California who were members of the Credentials Committee. All for naught, it turned out. “Joe, they’ve screwed you!” an NBC correspondent shouted to MFDP lawyer Joseph Rauh on Saturday, a few moments before he was scheduled to appear before the Credentials Committee. “My God, already?” Rauh responded. Convention managers, working hand in glove with the White House, put the Credentials Committee meeting in a room too small for more than one TV camera. Part of Rauh’s plan had been to attract large TV attention for the sufferings of the MFDP at the hands of Mississippi’s regular Democrats. But the revolutionaries kept doggedly on. Among them, farm worker Fannie Lou Hamer testified before the Credentials Committee about the privations–eviction and a savage beating by sheriff’s deputies—she had endured for trying to register to vote. But the White House privately forbade “that illiterate woman” from speaking to the open convention. It turned into a parliamentary free-for-all. Most of the regular Mississippi delegates would not take seats on the same floor with the MFDP ones, who refused to leave. All but three of the Mississippi regulars went home. The other three, and other Southern delegates who remained, did so at the abject pleading of the White House–and under threat of becoming pariahs in their states. Johnson, pretending to be above it all, helped aides fashion a settlement which certified just two MFDP members, meanwhile angering all of them by even spelling out which specific two would be certified. The South was enraged that there were any, while such black leaders as King and Andrew Young supported Johnson as by far better for African Americans than Goldwater. SNCC’s bloodied Mississippi partisans, by contrast, bitterly called for the seating of every MFDP delegate. Attacked from left and right, Johnson feared not just the Republican Goldwater but also two giants–George Wallace and Robert Kennedy–from opposite wings of his own party. The President briefly and abortively decided to resign. His depression was so profound that it elicited a private, written love-note of support from his wife, Lady Bird. But Johnson recovered his mental and physical muscles. His strong-arm tactics and promising future changes in the way delegates would be chosen pulled off a convention with a facade that glittered on-camera with feigned camaraderie and ended up nominating him by acclamation. But a lot of Southern seats were empty, and behind the facade the party’s sores festered and ran. Georgia Gov. Carl Sanders and Texas Gov. John Connally forecast a complete Southern exodus from the party. Johnson protested that no Southern state establishment had lost a single vote and that the MFDP at least deserved the two delegates the President’s negotiators had granted them. “These people (in Mississippi) went in and begged to go into the conventions,” Johnson told Sanders. “They’ve got half the population, and they won’t let ’em. They lock ’em out.” “They’re not registered,” Sanders doggedly maintained, ignoring the fact that they had been kept from registering by brandished baseball bats and worse. “Pistols kept ’em out,” Johnson said. Tenuously, Democrats had forged yet another hardly-holy bargain. Their President had been nominated. But in Mississippi the pistols still ruled.

[For more, see Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1998; ‘Racial Matters’: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960-1972 by Kenneth O’Reilly, Free Press 1989; An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America by Andrew Young, HarperCollins 1996; and Walking With The Wind: A Memoir of the Movement by John Lewis, Simon & Schuster 1998.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta