|

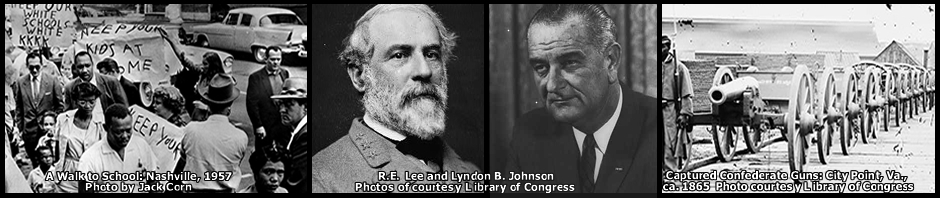

1864 U. S. Grant’s mammoth June crossing of the James River and his descent into Robert E. Lee’s backyard at Petersburg transformed the war in eastern Virginia into a trench stalemate in July–and shifted the focus to other fronts. In northern Georgia, William T. Sherman kept outflanking severely outmanned Joseph E. Johnston and pushing the Confederates backward. To relieve Grant’s pressure on Lee, Confederate Maj. Gen. Jubal Early took 10,000 men north from the Shenandoah Valley to threaten Washington. And in Washington, Abraham Lincoln balanced his refusal to accept anything but all-out victory by offering forgiving terms to a surrendering Confederacy. He emphasized his intended magnanimity by pocket-vetoing the highly punitive Wade-Davis Bill passed by Congress. One of the few outright Union triumphs during the month came near Tupelo, Miss., where dug-in Maj. Gen. A. J. Smith soundly whipped the smaller attacking forces of Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee and Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. On the month’s final day, the focus switched back to Petersburg. The Federals there exploded–then botched–a plot to dynamite a hole in Confederate lines wide enough to end the war. * After Joe Johnston’s Confederate defenders repulsed Sherman’s attack at Kennesaw Mountain on June 27, the Federals returned to flanking movements. The onset of July ended the rains that mired Federal supply roads and prompted the Kennesaw attack. Union forces and supplies could move more freely. By continually heading around Johnston’s flanks into his rear, Sherman kept forcing the Confederate backward. On July 2, Johnston quit Kennesaw Mountain, but during the week Union right wing commander James B. McPherson got around Johnston’s left and reached the Chattahoochee River, nearer Atlanta than Johnston was. Johnston quickly crawfished back to the river and crossed it on July 9. Sherman, now on Atlanta’s doorstep, spent July 10-17 massing supplies to besiege the pivotal rail hub. Then the Confederacy handed the Union a gift. Jefferson Davis, unable to see beyond personal friendship in judging subordinates and having disliked Johnston since the war’s outset, did not seem to see that Johnston was an impressive defensive tactician whose skillful retreats had brought his largely un-bloodied army to the imposing fortifications around Atlanta. There he should have been better able to make a stand. But he disliked Davis as much as Davis disliked him, and he stoutly refused to tell the Confederate president his plans. Finally, in mid-July, Davis sent a military emissary to Atlanta to try to find what Johnston was up to. The emissary, Gen. Braxton Bragg, was himself an example of Davis’s bent to let friendships rule personnel decisions. Davis had retained Bragg far too long as commander of the Army of Tennessee–and then kept him on as his chief adviser. On July 17, Davis relieved Johnston and replaced him with Hood, who swiftly began a series of disastrous Davis-urged assaults. In the battle of Peachtree Creek on July 20, some 20,000 of Hood’s men attacked 20,000 of Sherman’s, and Hood lost 4,796, Sherman 1,779. The battle of Atlanta on July 22 cost Hood 10,000 of the 40,000 he brought to the field, while Sherman lost 3,700 of his 30,000. The battle of Ezra Church on July 28 cost Hood another 5,000 men to Sherman’s 600. The Army of Tennessee could ill afford more such. * A June raid by Union Maj. Gen. David Hunter had plundered and burned the Virginia Military Institute, and Maj. Gen. Jubal Early was determined to avenge it. On July 2, Early and some 10,000 Confederates headed north from Winchester, Va., into Maryland. On July 6 an Early subordinate, Brig. Gen. John McCausland, a graduate and former instructor at VMI, demanded $20,000 from the residents of Shepherdstown, Md., in repayment for Hunter’s Shenandoah destruction. On July 8, Early himself demanded $200,000 at Frederick. A few miles south, Federal Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace gathered 6,000 men and blocked Early’s path to Washington. On July 9, Early attacked and routed Wallace at Monocacy, but Wallace had bought time to beef up the capital’s defenses. Early did not enter the Washington suburbs until July 11, but his appearance frightened residents and prompted hysterical newspaper headlines. At Silver Spring, Md., the Confederates burned the home of Francis P. Blair, adviser to presidents since Andrew Jackson. Then, at Fort Stevens in the District of Columbia, they provided firsthand combat viewing for President Lincoln himself. That, though, was it. Early realized he was too weak to do more than frighten, and he re-crossed the Potomac on July 14. His gambol would bring onto the Shenandoah Valley more powerful revenge than that which he had tried to wreak on Maryland. “If the enemy has left Maryland, as I suppose he has,” General-in-chief Grant wrote Chief of Staff Halleck, “he should have upon his heels, veterans, Militiamen, men on horseback and everything that can be got to follow…” Their mission, Grant said, should be “to eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they go…” * Obsessed with keeping the Confederacy’s most dangerous cavalryman off his lines of supply, Sherman sent yet another Union general after Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. A. J. Smith found his intended prey near Tupelo, Miss. Also at Tupelo, though, was Forrest’s immediate superior, Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, who asked Forrest to lead the Confederates in the impending battle. Forrest insisted that Lee do it. Forrest never explained why, except to say he was suffering with boils, but boils did not keep him from making a dangerous nocturnal visit behind Federal lines into Smith’s own camps. The marginally educated Forrest may have been suffering more from wounded pride. Lee had just been promoted to lieutenant general because he commanded the department in which Forrest had won the great victory at Brice’s Crossroads in June. And for more than two years, Forrest had endured marked lack of appreciation from other West Point-trained, aristocratic superiors before Lee. At Tupelo, Forrest nominally backed Lee’s unimaginative plan to attack the well-entrenched Smith, although some subordinates later said Forrest indicated to them he did not agree with it. Bearing no Forrest hallmarks, it was a head-on assault, the kind Forrest never launched without joint attacks from the flanks. When the battle opened on July 14, Forrest began high-handedly changing the plan, re-gathering some of the men who had fallen back but then refusing to send some of his own troops forward into the obvious slaughter that had greeted their predecessors. Smith won the battle, losing fewer than 700 casualties from his 14,000 men while Lee and Forrest lost 1,350 of their 9,000. But Smith, saying his troops’ bread supply had spoiled, quickly headed back to Memphis, with Forrest’s men dogging the Federal heels. * The idea of the Crater was hatched by Pennsylvania troops who had been coal miners, and it turned out not to be a bad one. Its execution, however, was wretched. The plan was for a division of U. S. Colored Troops, the first such troops to be employed in combat in Virginia, to lead a drive through a massive hole blown in the Confederate lines at Petersburg. Four tons of dynamite were to be exploded at the end of a tunnel dug by the miners. At the last minute, on July 30, the plan changed. Grant doubted it could work, and Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade replaced the fresh USCT division, which had been drilled on its role, and substituted a white unit. Grant later told Congress that he and Meade feared public condemnation of a massacre of the black troops if the plan failed. At first, it succeeded. The blast blew a 170-foot-wide hole in the Confederate fortifications that was at least 60 feet wide and 30 feet deep. Then, though, the attackers had to get across or around the big hole. And no officer had considered the difficulty of even how to get over their own eight-foot parapets. Protected from Confederate fire by a covered path, their troops had to advance from the rear to their own ramparts in column of twos. So they moved into the loose dirt of the debris-covered crater only in squad-size units–where they were virtually trapped by the hole’s near-vertical sides. And the Confederates, quickly recovering, poured rifle and cannon fire down into the breach—just as the USCT division charged in with fixed bayonets. Having heard newspaper reports of the April massacre of black troops at Fort Pillow, Tenn., by Forrest’s cavalry, they came on like madmen. One of their white Union officers recalled: “There was a half determination on the part of a good many of the black soldiers to kill (Confederates) as fast as they came on them. They were thinking of Fort Pillow…” Some Confederates captured in the onrush begged the white officers not to let the black troops kill them. Meanwhile, some officers of the counterattacking Confederates yelled “Kill the damned niggers!” Many members of the USCT division gave Confederates no quarter, as many of Forrest’s troops had done to USCT units at Fort Pillow. And Confederates, seeing blacks in uniform for the first time, outdid themselves at slaughter. In and around the Crater raged a hand-to-hand fight to the death. The quick reaction of Confederate Brig. Gen. William Mahone, coupled with the ineptitude of Union two Union division commanders who stayed behind drinking in a bombproof, doomed what could have been a huge Federal victory. Instead, it became another notable instance in the long series of American racial bloodbaths. [For more, see The Civil War Almanac by John S. Boatner, Bison Books 1982; The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001; War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Government Printing Office 1880-1891, series 1, vol. 39; and No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, 1864 by Richard Slotkin, Random House 2009.] |

1964 Suddenly there was a 1964 civil rights law. On July 2, after insisting that guaranteeing African American rights would take away those of other Americans, the vociferous congressional opposition gave up. President Johnson, seeming almost to fear that Congress might change its mind, did not wait for the quintessentially symbolic signing occasion afforded by the upcoming Independence Day. He rushed to pen the bill into law on the evening of the same day it passed. Present for the accompanying press conference were national TV cameras and a few people who had worked hard for this milestone–including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., labor leader George Meany, and of course Johnson himself. Also present was one who had surreptitiously resisted it at almost every step: FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. There then dawned a promising, fleeting, and utterly naive moment of belief that all had changed. On July 3, word went out that the recalcitrant businessmen of St. Augustine, Fla., had given up and agreed to admit black patrons. In Albany, Ga., which for years had defeated desegregation efforts by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and Dr. King, a pastor began blessing integrated meals around town. Two elite hotels in Jackson, Miss., and even one in bitter Birmingham allowed African Americans to register. Then dogged and dangerous bigotry reasserted itself. On July 4, the Ku Klux Klan rallied in downtown St. Augustine, and within the week Ku Klux intimidation had led most of the proprietors to rethink. In Greenwood, Miss., where movement veteran Robert Moses sternly forbade his student charges from neglecting their Freedom Summer work to test the new law in restaurants and movie theaters, a lone local named Silas McGhee succeeded in buying a ticket to the Leflore Theater’s Sunday matinee on July 5. But he had to quickly flee from other angry patrons to the manager’s office and be taken home by police– after they satisfied themselves he was not a part of the Freedom movement. More than 150 miles south of Greenwood at Hattiesburg, ominous white-occupied vehicles continually passed five new SNCC Freedom Schools that had been designed for 100 teenagers and were being overflowed by more than six hundred people aged eight to eighty-two. Incidents erupted. On July 6, a sniper shot a young black woman in the stomach as she attended a voter registration meeting in Moss Point, Miss. In Hattiesburg on July 10, a Cleveland rabbi walking to lunch with two young Stanford volunteers was beaten with fists and a lead pipe, and he and the volunteers were all hospitalized. In McComb on July 8, nocturnal visitants bombed a Freedom House opened by eight volunteers, the first Movement presence since state legislator Eugene Hurst was not even arrested, let alone tried, for his 1961 murder of black farmer Herbert Lee. Nevertheless, the Freedom School in McComb opened–and enrollment surged from 35 to 75 after two black churches were bombed. The one white couple who reluctantly agreed to listen to the volunteers’ message had their house surrounded on July 17 by a militia group that proceeded to stalk them and poison their dog–despite the fact that they were parents of the reigning Miss Mississippi. In Greenwood on July 15, SNCC worker Stokely Carmichael was arrested for holding a mass meeting. He later recalled his witty reply to a lawman’s dismissive insult. “That’s right, niggers don’t do nothin’ but gamble and drink wine,” Carmichael wryly agreed. “But who taught us how?” The next day Greenwood police ripped apart the “One Man/One Vote” signs carried by some of 111 demonstrators who showed up to picket the courthouse. The officers hauled the 111 to jail. Alabama was not to be left out. In Selma, four new volunteers from Northern colleges decided to toast the new civil rights law at a local drive-in restaurant on Independence Day. Police cars quickly showed up, and cattleprod-wielding Sheriff Jim Clark took the four to jail. Soon afterward, Clark chose to close the town’s two movie theaters after black crowds surged out of their balconies into main-floor seats traditionally reserved for whites. The next night, the sheriff and 50 specially-deputized men charged into a black church and broke up a movement mass meeting–a “riot,” Clark called it–by throwing tear-gas canisters and wielding nightsticks. Then John Lewis, chairman of SNCC, arrived. The next day, July 6, Lewis led 70 hopeful voter registrants to the courthouse. Twenty changed their minds when challenged by Clark, but Lewis and the others marched to jail singing freedom songs while Clark repeatedly struck them with the electricity of the cattle prod. A local judge then declared it illegal for “three persons or more” to assemble “in a public place” if they did so under the auspices of Lewis’s SNCC, Dr. King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, or 39 other organizations dedicated to the cause of black rights. The Selma newspaper headlined Alabama Gov. George Wallace’s contention that the new law was a “fraud” and gave much space to his assertion that “liberalism” was “destroying democracy in the United States.” Back in St. Augustine on July 16, Dr. King decried the setbacks that had followed the new law’s signing day–and the sudden, alarming growth of racism in the party of Lincoln. * The Republican convention met in San Francisco beginning on Monday, July 13. Civil rights activists picketed as 1,308 white delegates and just 14 black ones gave their presidential nomination to hard-right U. S. Sen. Barry Goldwater of Arizona. The campaign was already shattering traditional political alliances that had stood for a century. The so-called “Solid (Democratic) South” suddenly rallied to Goldwater’s steel-cored conservatism and his credo, “Extremism in the cause of liberty is no vice!” The atmosphere was distinctly unwelcoming to blacks. For the first time since Reconstruction, Southern GOP delegations rid themselves of every African American. Baseball giant and black hero Jackie Robinson said, after observing the convention from its floor, “I now believe I know how it felt to be a Jew in Hitler’s Germany.” The convention’s racist bent was all the more surprising because more than 80 percent of the party’s representatives in Congress had just voted in favor of the new civil rights bill. President Johnson couldn’t have passed it without them. But now their moderation was on the wrong side of their party’s evolving history. The Republicans’ self-whitening was happening because Johnson, perhaps to try to convince the world that as President he meant to be more American than Southern, had been granite-like in his determination to pass the civil rights bill. On July 10, at his insistence, J. Edgar Hoover had had to fly to Jackson to open Mississippi’s first full-time FBI headquarters. While there, Hoover agreed with a reporter who suggested that the three civil rights workers missing in Mississippi since June were dead. Perhaps his generation’s most astute politician, Johnson well knew the likely political cost of his effort. He told young aide Bill Moyers that he had handed the South to the GOP “for your lifetime and mine.” *

At the beginning of the fourth week in July, Dr. King headed to Mississippi and a mass meeting in embattled Greenwood. Thanks to Johnson, he had a convoy of FBI protectors. This enraged Mississippi lawmen, because Hoover had long maintained a public policy against protecting civil rights workers–not to mention a private personal disinterest in death threats to King. The civil rights leader went first to Greenwood, where the 111 demonstrators had just been released after six days in jail. He spoke to a poolroom gathering in the afternoon and two mass meetings that night–while over the town’s black communities a small airplane dropped Klan literature dubbing the high-profile visitor the “Riot King.” The black crowds seemed wondering rather than wildly enthusiastic. Now and then a King remark prompted an exclamation of “De Lawd,” the wry SNCC byword denigrating King and the headlines he generated. SNCC’s veterans, who lived in daily fear for their lives amid a virtual media blackout, shook their heads at his retinue of FBI protectors and media. “It is a shame that national concern is aroused only after two white boys are missing,” John Lewis had observed. The next day, July 22, King flew to Jackson for another speech, then on July 23 headed to Tougalou College to confer with Bob Moses about Freedom Summer. He tape-recorded radio spots for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party before returning to Jackson on July 24 for a history-making TV appearance in behalf of the MFDP. It was the state’s first black TV program. From Jackson, the King caravan headed to the wilds of rural Neshoba County. For days, the FBI had been traversing Neshoba by foot and helicopter, aided by a young black man whose identity was concealed by a cardboard box over his head, perforated by eyeholes. Back in May, this young man had been arrested on charges of asking a white girl for a date. In jail, he said, deputies of Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey beat him, then released him about midnight to Klansmen waiting outside. The Klansmen conducted him to what they said would be his gravesite if he didn’t confess his “crime.” FBI agents had hoped that the area he showed them might hold the bodies of the three SNCC volunteers missing since June. The agents suspected that a similar jail-to-Klan exchange led to the trio’s tragic end. No SNCC bodies turned up where the young man led them, but the FBI’s presidentially-mandated search was getting too close for local comfort. Sheriff Rainey protested to Hoover’s Washington office over King’s FBI escort and asked what had become of Hoover’s public promise not to protect civil rights workers. “We believe that the protection of King could have been adequately handled by state and local law enforcement officers,” Rainey complained. [For more, see Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1998; In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s by Clayborne Carson, Harvard Press 1981; Walking With The Wind: A Memoir of the Movement by John Lewis with Michael D’Orso, Simon & Schuster 1998; ‘Racial Matters’: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960-1972 by Kenneth O’Reilly, Free Press 1989; and An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America by Andrew Young, HarperCollins 1996.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta

We tend to think that the Civil War was really over after Gettysburg and Vicksburg and that with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the battle against segregation and racism was over. Events in the last half of 1864 and 1964 tell a different story. Much blood was yet to be shed. And, 150 and 50 years later, respectively, are the issues really resolved? I think not. Les Lamon