1862One of the Civil War’s most pivotal months began as unpromisingly as ever for the Union in the East. President Lincoln continued trying to push his obstinate general-in-chief, George McClellan, into actually fighting. McClellan disagreed with Lincoln in public over the President’s wish for a straightforward lunge at Richmond. McClellan favored a more roundabout, and thus conveniently less immediate, strike by water down the Chesapeake Bay to come at the Confederate capital from the coast. McClellan’s heel-dragging was by no means all. Lincoln’s distress was magnified by the serious illness of his beloved next-to-youngest son, Willie, 11, who had come down with typhoid fever. Lincoln was up at all hours comforting and administering medicine to the boy. His wife, Mary, was frantic with worry. In Richmond, the Confederate Congress was debating whether free blacks could enlist in the Confederate Army; the consensus on that, backed firmly by President Jefferson Davis, was no. The Richmond Examiner called for the reenlistment of soldiers whose brief first commitments had expired, and most were not likely to be enticed back in by the prospect of serving alongside slaves. The Confederates had many slaves in their camps working as cooks, teamsters, construction men, and personal servants. But formalizing their position in the ranks and giving them rifles would have been tantamount to declaring them the equals of whites – not to mention dangerous to the givers. That in turn would have seemed to throw away the principal point of the war. Bottom line, it was not only being waged to keep them enslaved but also to enlarge the territory where chains would remain their lot forever. More of the Confederate coast – and the waterways enabling Confederate merchant ships to get to open sea – had come under imminent threat. General Ambrose Burnside’s 15,000 troops landed on Roanoke Island off North Carolina on the 7th. On the 8th, the outnumbered Confederates there surrendered, losing the Confederacy its access to and egress from the Albemarle Sound. West of the Appalachians, the Confederates were peering across the brink of disaster. The January 19 battle at Logan’s Crossroads or Mill Springs in Kentucky, and the rout of the little Confederate army there, had left Cumberland Gap – and the road to Knoxville and the vital East Tennessee railway linking Virginia to Georgia – virtually undefended. The Logan’s Crossroads rout was so profound and communications with the scattering army in eastern Kentucky so bad that Confederate western commander Albert Sidney Johnston did not learn of the defeat until three days later. He then immediately informed Richmond: “If my right is thus broken as stated, East Tennessee is wide open to invasion – or, if the plan of the enemy be a combined movement upon Nashville, it is in jeopardy.” * * * Nashville was indeed endangered. Lincoln did not realize it yet, but he had finally found a fighting general. The obscure brigadier Ulysses S. Grant, Federal district commander at Cairo, Illinois, not only would fight, he hungered to, and his eagerness was redoubled now. In late January, sensational charges of chronic alcoholism had been filed against him in the Union chain of command. His superior, Federal western co-commander Henry W. Halleck in St. Louis, was frantically trying to get a more experienced – and more presentable – officer promoted to lead Grant’s army down the Mississippi River against the vaunted Confederate “Gibraltar” at Columbus, Ky. Grant probably did not know about Halleck’s efforts to promote a replacement, but the commander’s contempt for Grant had been made all too plain. Halleck was a rich and venerated military intellectual, Grant a known drunkard whose taste for liquor had led him out of the prewar army into poverty. He had barely gotten back in after the firing on Fort Sumter. With his job imperiled in February 1862, circumstances saved him. A Federal boat foray down the Tennessee River disclosed a far more vulnerable objective than Columbus. A Confederate installation called Fort Henry, erected just over the border of the Volunteer State to prevent Union incursions on the Tennessee, could be decimated by two ironclad gunboats, Union Brigadier General Charles F. Smith predicted. Grant, anxious to attack something and win a victory while he still had an army, beseeched Halleck to let him assail Fort Henry. His request accompanied another from the naval commander on the rivers, much-respected Flag Officer Andrew Foote, and Halleck let them go ahead. If they won a victory it would redound to department commander Halleck – who, politically battling his western co-commander, Don Carlos Buell, in Louisville, needed one. Buell’s men had won the victory at Logan’s Crossroads. Grant’s steamboat-borne troops and Foote’s gunboats embarked on Feb. 1. They captured Fort Henry on Feb. 6 in about two hours. Well, Foote’s gunboats did. The vessels battered Henry’s walls with head-on fire and accepted the fort’s surrender before Grant’s infantrymen could slog through the surrounding mud to get there. For all its importance, Fort Henry appeared to be no great prize. It was in the process of being inundated by the flooding Tennessee as the battle progressed, and only about 100 Confederate artillerists were found inside when the fighting ended; the rest, some 2,600 infantrymen, had escaped before Grant could surround the place. They had fled in disorder to Fort Donelson, 12 miles east on the Cumberland River. Foote’s gunboats meanwhile raced on southward up the Tennessee, into northern corners of Alabama and Mississippi. The floodgates of Union invasion had been kicked wide open. Grant, doubtless abashed at having captured an all-but-empty fort, wired Halleck that he would attack Fort Donelson two days later, on Feb. 8. Halleck responded with neither yea nor nay. That way the inveterate military politician could claim the resultant victory or disavow the defeat. Then rains set in, drowning the roads. Grant could not put his army on the two routes to Fort Donelson until Feb. 12. He did so in the face of continued ominous diffidence from Halleck’s headquarters in St. Louis. * * * Fort Donelson turned out to be larger than Grant had anticipated. Its entrenchments extended nearly three miles, fronting not only the fort itself but also the little town of Dover and its riverboat landing – to which supplies and reinforcements could be brought downstream from Nashville. And rumor had it that the Confederates already had more men inside their trenches than Grant had outside. None of this gave Grant pause. He ordered up more men from Fort Henry, requested others from Halleck to hold Henry, and spent the 13th extending his lines around Donelson while waiting for Foote’s presumably invincible ironclad gunboats to go back down the Tennessee and up the Cumberland. The gunboats arrived north of Donelson that night, and the next day, Feb. 14, Foote attacked with four ironclads and two timberclads. But this was not Fort Henry. This fort sat 100 feet above the Cumberland instead of waterside, and its guns nearly blew Foote’s craft out of the Cumberland. They wrecked two of the ironclads and damaged the others, while the vessels, having to continually adjust their guns to the high target as they advanced, did no damage to the fort. Foote’s sailors had to spread sand on the decks just to keep their feet from slipping in the blood. Foote himself was wounded. Unable to come to Grant, Foote requested that the general come to him the next morning, Feb. 15, to discuss strategy. So Grant rode an icy road several miles north of his lines to where Foote’s boats were anchored, only to find that Foote was determined to take the vessels back to Illinois for refitting. He would return in ten days, he said. Grant did not know if Halleck would allow him ten more days. And he had an even worse problem, as it turned out. When he made it back to his lines after an absence of several hours, he found his right had been crushed and rolled back onto the center by a powerful Confederate offensive. Then, though, the reputed sot showed himself to be a general of unique talent and grit. With his right dissolved and his supposed aces in the hole, the ironclads, now nullified and useless, he kept his head clear enough to notice something important: the Confederate attack had ceased. Its field commander, Brigadier General Gideon Pillow, had ordered the Confederates back to their trenches to collect the materiel with which they planned to march to Nashville. In thus retiring from the field, they all but abandoned the ground they had spent seven hours and hundreds of lives to gain. Grant did not know Pillow’s plan, but he did recognize that his foe was not trying to win the battle; rather, he was trying to find a way out of it. Contrary to what virtually any other major Union commander would have done at this stage of the war, Grant did not retreat or dig in where he was. He counterattacked all along what remained of his line. By dusk his troops had penetrated the Confederate trenches, and overnight the Confederate generals held a hapless meeting that would have been comical had it not wasted so much blood. Far from unanimously, they decided to surrender. The timid nominal commander, Brigadier General John Floyd, gave the command to Pillow, who passed it to the third in command, Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner, the only trained soldier of the three. Buckner, who had let his contempt for the blithely arrogant and minimally competent Pillow cloud his judgment, seemed set on surrender after Pillow made the monumental mistake of withdrawing from the battlefield. Floyd and Pillow then fled, leaving Buckner to consign himself to captivity. He asked Grant for terms, and Grant, on the advice of Brigadier General Charles Ferguson Smith, replied that he would accept no terms but unconditional surrender. He added, with truth: “I plan to move immediately upon your works.” Fourteen thousand Confederates surrendered, and thousands more just walked away in the confusion of the largest capitulation the American continent had yet seen. Grant’s convenient initials prompted newspapers to label him “Unconditional Surrender,” and Lincoln immediately promoted him to major general. * * * But Lincoln’s February gladness was tempered by deepest sorrow. On the 20th, his son Willie died, sending Mary Lincoln – already stressed by having several half-brothers and a brother-in-law in the Confederate army – into haunted mental imbalance, It transformed the White House into a funereal chamber of grief. As for the Confederates, western commander Albert Sidney Johnston recognized too late that his decision to put Floyd, Pillow, and Buckner in charge of Fort Donelson was a personnel disaster so far unparalleled in this war. As it turned out, the only first-class Confederate commander there had turned out to be a lieutenant colonel of cavalry: N. B. Forrest, who came out of the battle with fifteen bullet marks on his coat. Forrest, like Grant, had no pedigree. He was marginally educated and his principal prewar occupation, which had made him rich, was trading slaves in Memphis and up and down the Mississippi River. His former vocation was now in growing danger of extinction in America; that was evidenced by an event this very month. On Feb. 7, the State of New York had dispensed to Nathaniel Gordon, a ship captain charged with participation in the illegal African slave trade, a punishment it had not handed out to a seagoing slave-transporter in nearly a half-century. It sentenced him to hang. (For more information, see The Civil War Almanac by John S. Boatner, ed., Bison Books 1982; The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, volume 7, Government Printing Office 1882; The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant, volume 4, by John Y. Simon, ed., Southern Illinois University Press 1972; A World On Fire: Britain’s Crucial Role in the American Civil War by Amanda Foreman, Random House 2010; and The Life and Wars of Gideon J. Pillow by Nathaniel Cheairs Hughes Jr. and Roy P. Stonesifer Jr., University of North Carolina Press 1993.) |

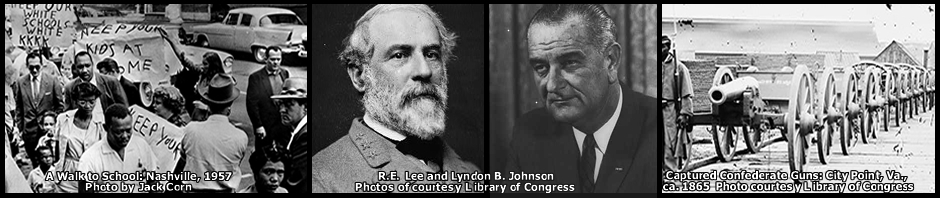

1962U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy left on a world tour on Feb. 1. Major developments in both Washington and the Deep South began unfolding immediately in his wake. The day after his departure, Acting Attorney General Byron White took a stance Kennedy would not have. He met with a subordinate FBI official regarding a Jan. 8 Bureau memo that Kennedy had discounted. The document reported New York attorney Stanley Levison, close advisor to civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., to be a secret member of the Communist Party. It added that King’s meetings with the Kennedys were likely sullying the highest levels of the Administration with Communist influence. The official reported to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover that White wanted to act on the matter. He said White wished to examine the FBI’s information on Levison in the hope of finding facts that would rouse the Administration out of its lethargy on the issue. Hoover was the most dedicated kind of non-Communist. He had been so since the 1920s, which had been set a-tremble by the 1917 Bolshevik revolution in Russia. He had increased his anti-Communist animus during the late 1940s and early 1950s, which rocked with Communist spy scares encouraged by Senators Joseph McCarthy of Wisconsin and Richard M. Nixon of California. The Cold War with Russia in the later 1950s and early 1960s did not diminish his fear. White’s reaction, though, was more than Hoover had hoped for. The information the FBI had on Levison was hardly current or particularly alarming. Its latest bits were five years old. The Bureau also had tried to recruit Levison as an informer, which it hardly would have done with someone who was deemed dangerous. And there was no indication that either Levison or his supposed fellow traveler, King, had backed policies of the Communist Party, domestic or foreign. Hoover naturally did not want to disclose this. He had no alternative but to sidestep. He forbade release of any such information to White. Hoover thus implied that the information on Levison was too vital to national security to release. On Feb. 14, he sent White and White House representative Ken O’Donnell summaries purporting to detail King’s contacts with American leftists. When Robert Kennedy returned on February 27, Hoover gave him an embarrassing homecoming. The upshot was unmistakable. Hoover must be handled with extreme care. But Kennedy’s international jaunt had strengthened his consciousness of the importance of desegregating the South. As he put it afterward: “There wasn’t one area of the world that I visited…that I wasn’t asked about the question of civil rights.” * * * Martin Luther King’s work in that very area was meanwhile becoming more productive than ever. He finally was getting the Kennedy-recommended South-wide voter registration effort going in a huge, cohesive way. Transforming the civil rights movement, the campaign took dead aim at the foundation of Southern white supremacy: the vote. The sit-ins and Freedom Rides directed at restaurants, movie theaters, buses, and trains would continue, but they would become more symbolic, subordinate targets. The registration strike at the core of institutional Southern racism, grasping for the liberty so long overdue Dixie’s people of color, began systematically rolling on Feb. 2. That day, the various division leaders of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference gathered for an SCLC meeting in Atlanta. Organizational wizard Jack O’Dell, now dividing his time between New York and Atlanta, led business sessions setting up and standardizing a sprawling plan. Its scenario called for no less than an assembly line of sectional revolution:

The plan was ambitious. It focused on all of the 188 Deep South counties where blacks outnumbered whites. To succeed, it had to. The planners knew that a few small pockets of successful registration could soon be overwhelmed by the monolithic white political establishment: governors, legislators, and mayors protected by a vicious front line of sheriffs, deputies, highway patrolmen, and, less officially, Ku Klux Klansmen. To endure, what had to be built was a South-wide black electorate, a power bloc of ballot-box muscle whose wishes the region’s white office-seekers could no longer flout. Only then, for the first time since Reconstruction, could African Americans begin to enjoy the blessings of constitutional protection promised them after the Civil War. * * * Immediately after the Feb. 2 SCLC meeting, King left on what he termed a “People-to-People” tour. The object, he said, was to assemble a “Freedom Corps.” To get its first volunteers, he went to the state in which African Americans arguably needed it worst: Mississippi. He spoke first at a Baptist church in Clarksdale, then toured Delta counties to emphasize that this was much more than a showboat swing. He spoke everywhere from churches to country stores and out-of-the-way, wide places in unpaved roads. In little Sherard, Mississippi, he regaled an audience of just one, an aging farmer who had walked 13 miles to meet this already-legendary 33-year-old preacher who was trying to finally make the South livable for black people. In three days spent in one congressional district – whose byroads had been preliminarily worked by Freedom Ride giants Jim Bevel and Diane Nash – he recruited 150 people to attend the Clark-Cotton citizenship school in Georgia. These then were expected to return to their communities to similarly instruct their neighbors. The recruited volunteers were mostly illiterate, and no wonder. The South had done all it could to keep them that way. Its segregated, “separate but equal” education credo gave African American schools mostly just desks and books cast off from the white institutions. Thanks in considerable part to this educational discrimination, most of the black population lived in such poverty that children could only attend even these poor schools when they were not needed in the fields. Clark and Cotton had only a week to inculcate each class of these people with the skills of a citizenship whose privileges they had been denied. The two women started with information the students said they wanted to know, reasoning that they would learn it quickest. Evolving their techniques on the job, Clark and Cotton moved on to things the students would have to know, using newspapers, street signs, and common state and federal government forms to familiarize them with words and expressions they would need to know to register. From Mississippi, King went on to similarly focused tours of Georgia and South Carolina, and on Feb. 22 the Voter Education Project was announced to be up and running. It obviously was. Upwards of 1,000 people had signed up for the Freedom Corps. The SCLC was proving itself worthy of the funds Andrew Young was methodically extracting from Northern philanthropic foundations. He got three initial grants totaling $163,000, along with pledges that this was just a down payment on further largesse. * * * Jet, the largest and most influential African American weekly magazine, headlined the SCLC effort. It described King’s odysseys as more like those of a political campaign than a religious revival trail. It was, Jet said, the greatest move toward the gaining of black rights in the South since Reconstruction. All this could not go unnoticed in the wider black community, where it was not always accepted with wholesale admiration. Members of SNCC had grabbed the Freedom Ride flag back in May and thrust it through the doors of Southern buses and bus stations after CORE, benumbed by the Anniston bus bombing and the Montgomery Klan riot, temporarily abandoned it. Yet they felt their shed blood, which had brought a national spotlight to the viciousness of segregation, was unappreciated by King’s SCLC. SNCC’s students could not forget that when King quickly exited the Albany jail in December and held a press conference, he banned them from it, despite the fact that they had predated him in Albany. Cordell Reagon said he doubted King’s Albany predecessors appreciated “getting their balls busted day in and day out, and then you don’t even get to speak on it.” Reagon knew they didn’t; he was one of them. John Lewis, who already had bled for the cause and would do so repeatedly again, saw the comparatively well-financed SCLC as trying to work for the “masses” independent of their input and their suffering, whereas SNCC was the resource-poor front line of the struggle, sharing the trials of the common people. SNCC’s volunteers, he felt, resembled the first Christians, continually daring the dangers of enemy country, “not knowing where we were going to stay from one night to the next, where or what or if we were going to eat. “We couldn’t be certain we were even going to return.” (For further information, see Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1988; An Easy Burden by Andrew Young, Harper-Collins 1996; Walking With the Wind by John Lewis, Simon & Schuster 1998; The Children by David Halberstam, Random House 1998; “Racial Matters”; the FBI’s Secret File on Black America 1960-1972 by Kenneth O’Reilly, Free Press 1989; and In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s by Clayborne Carson, Harvard University Press 1981.) |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta