1862 Don Carlos Buell The two warring American nations each had reason to rejoice—somewhat—as the new year opened. On January 1 in Provincetown, Massachusetts, Confederate commissioners John Slidell and James Mason, released from U.S.custody, boarded a British ship bound for Europe. That meant the Confederate States of America’s chosen representatives would soon be in Britain and France to push its pleas for European recognition and aid. But the Union’s release of the pair also defused the crisis that had threatened to put Washington at war with England for kidnapping the two emissaries off the British ship Trent back in November. President Abraham Lincoln could thus breathe easier on that front, but on few others. Congress and the Northern public were pressuring him to produce military progress against the Confederacy. On December 31, he hopefully wrote commander Henry W. Halleck in Missouri to ask if Halleck and Don Carlos Buell in Kentucky were thinking “in concert”? They were not. They were trying to out-politick—but not out-fight—each other. On January 6, some senators asked Lincoln to fire George McClellan, his dashing do-nothing of a general-in-chief. Lincoln refused. But, increasingly anxious to show forward motion, he suggested to Buell that he advance from eastern Kentucky and relieve “our friends” in East Tennessee. The “friends” had burned several strategic railroad bridges there in November, and now these loyalists were enduring a crushing Confederate crackdown. By that time, Buell was already taking a step in that direction. On December 29, he had given Brigadier General George H. Thomas the go-ahead for a New Year’s Day advance toward Confederates guarding Cumberland Gap, the gateway into East Tennessee. But the move was half-hearted on Buell’s part. Before leaving Washington to take the Kentucky command, he had seemed to agree to make an East Tennessee push, but on arriving in Kentucky he had become less sanguine. Thomas, by contrast, had been volunteering to lead an East Tennessee strike. Like his close friend McClellan, however, Buell claimed his troops were unready. Halleck, meanwhile, was focused on quelling local rebellion in Missouri. On January 9, Lincoln discussed the lack of Buell-Halleck cooperation with McClellan–to no more avail than when he brought up McClellan’s own reluctance to fight. In vain, McClellan pushed Buell and Halleck to do what McClellan was unwilling do himself: fight. The Union Congress meanwhile spent much of January considering petitions to end slavery–not just in the seceded states but throughout North America. They included measures to compensate owners for the emancipation of their slaves, colonizing the freed slaves somewhere outside North America, and various gradations of these two ideas. For President Lincoln, there was one bright spot in his otherwise gloomy offensive picture. On January 11, one hundred Union ships landed 15,000 troops in North Carolina. Commanded by General Ambrose Burnside, they established another coastal foothold, augmenting the beachhead already made on Port Royal Sound between Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia. On January 13, Lincoln wrote to both his western commanders, Buell and Halleck, urging concerted action. He said he wanted to pressure the Confederates with larger armies at various points simultaneously. For the time being, as it turned out, he had to settle for just one army at one point. George Thomas, with some 5,000 troops, was now zeroing in on the 4,000 sitting ducks that the hapless Confederate General Felix Zollicoffer had incompetently positioned at Beech Grove, Kentucky, in a bend on the north side of the Cumberland River opposite the hamlet of Mill Springs. Zollicoffer had thought the position a good one because the surrounding river bend protected his army on three sides. By the time he realized that the surging stream actually trapped him, winter rains had lifted its level so high he could not comply with superiors’ alarmed orders that he re-cross to the south side; he had no boats large enough to transport his artillery, horses, and wagons. Brigadier General George B. Crittenden, a new Beech Grove commander supplanting Zollicoffer, had begun cutting timber to build the necessary boats when he learned Thomas was approaching. Crittenden decided to try to surprise-attack Thomas, whose units were reported strung out on roads that the recent rains had converted to troughs of mud. Just past midnight on the cold and rainy morning of January 19, Crittenden headed his Confederates toward Thomas’s camp nine miles north at a crossroads bordered by the farm of a family named Logan. The roads were so wretched that Crittenden’s men had to wade water and mud a foot deep. It was 5:30 a.m. before the lead units encountered Federal cavalry pickets a mile or more south of Logan’s, and the rest were stretched out for three miles behind. Most of the entire column carried flintlock muskets requiring priming powder that was difficult to keep dry in the downpours. Amid dismal rain and the fog of gunsmoke, the two armies slugged it out for three and a half hours. Zollicoffer, a near-sighted ex-newspaperman and ex-congressman who now commanded one of Crittenden’s brigades, was shot to death when he blundered into Union lines. The Confederate muskets operated so poorly that many men got off no more than a dozen shots over the three and a half hours, and some were seen breaking their guns on fences in desperate frustration when the weapons would not fire at all. As the tide of battle, which had ebbed and flowed, now swept them backward in a flood, the Confederates—a few of whom had entered the army just a few days earlier—fled back down the road toward Beech Grove. Going back they made better time than they had coming forward, leaving behind a mired cannon and innumerable knapsacks that would have slowed their stampede. The Federals pursued slowly, stopping to forage hungrily through the Confederate knapsacks. When they finally reached Beech Grove late in the afternoon, they had time only to shell the place before darkness fell. The idea of sending in a surrender demand did not occur to Thomas, he acknowledged later, and Crittenden managed to cross his troops to the Mill Springs side of the Cumberland in the night on a small steamboat called the Noble Ellis. Their equipment and transportation animals, unable to be carried by the little boat, were left on the north bank to be taken by the Federals: 11 pieces of artillery, 150 wagons, and more than 1,000 horses and mules. In the battle, Thomas had lost 39 men killed and 207 wounded, while the corresponding Confederate tallies were 125 and 404. But even the casualties and mountains of materiel did not constitute all the Confederate losses. In the subsequent scattering retreat through the bleak and inhospitable mountains to Gainesboro, Tennessee, many more men, starving, simply deserted and went home. The battle—variously referred to as Mill Springs or Logan’s Crossroads—is all but unheard-of now, but it was vastly important at the time. It wrecked the right wing of the long tenuous line Confederate western commander Albert Sidney Johnston had strung across Kentucky from the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River, convincing Johnston that he was going to have to retreat from southern Kentucky. Johnston, based near that line’s center at Bowling Green, was still deciding how to do that when Federals under Henry Halleck began conducting ominous demonstrations and scouting forays to his left. In the third week of January, Halleck’s minion, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant at Cairo, Illinois, led a week-long foray into western Kentucky on the roads leading to the powerful Confederate fortress at Columbus on the Mississippi. Meanwhile, Brigadier General Charles F. Smith at Paducah rode a timber-clad gunboat to the environs of Fort Henry on the Tennessee River at the Kentucky-Tennessee border. He returned to report it vulnerable. In Washington, Lincoln was becoming desperate for more battles in more places to capitalize on the Mill Springs momentum. On January 27, he issued his naïve General Orders Number One, mandating simultaneous forward moves by all Federal land and naval forces on February 22 if not sooner. On January 30, Slidell and Mason arrived in England, but to little avail. The next day, Queen Victoria herself reiterated that Britain remained neutral in America’s Civil War. This affirmed that the so-called Trent Affair had not damaged U.S.-British relations beyond repair. That was bad news for the Confederacy. [For more information, see The Civil War Almanac by John S. Bowman, ed., Bison Books 1982; Lincoln by David Herbert Donald, Simon & Schuster 1995; The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001; History of the Twentieth Volunteer Regiment, C. S. A., by W. J. McMurray, Regimental Publication Committee 1904; The Old Nineteenth Tennessee Regiment, C. S. A., by W. J. Worsham, Paragon Printing Co., 1902.]

|

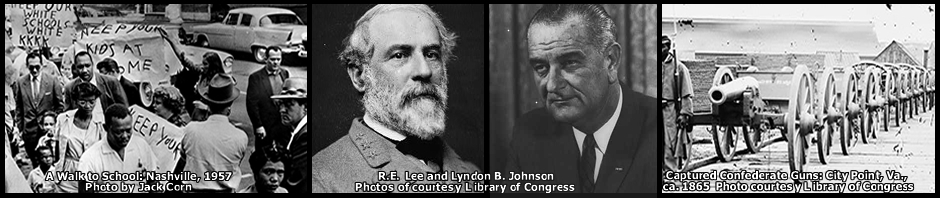

1962A New York Times article of January 20, 1962 reported that John and Jackie Kennedy had given average Americans “a much clearer idea of what it must be like to have everything.” For most, the contrast between themselves and the First Couple was stark. This was especially true of those imprisoned in America’s dark, dreary, and dangerous economic basement: African Americans in the South, imprisoned in bitter, perpetual want by iron-fisted Jim Crow laws that denied them all hope of progress. Most had no vote with which to try to improve their prospects. The few who did could only cast it in such a cause at the risk of their lives. Few if any, of course, ever saw the New York Times, which many would have had trouble reading had it landed on their homemade doorsteps. The South’s so-called “separate but equal” public education made a ludicrous mockery of fairness. Yet President Kennedy, son of the super-rich, represented a ray of hope to these, his financial opposites. Although his election had come, and only come, with the aid of white segregationist Democrats in the South, his administration was awakening to the shame of a nation which, while imposing legalized abject deprivation on a whole race of its people, hypocritically claimed to the world that it provided liberty and justice for all. To reach this point, though, Kennedy had to undergo a transformation. Only grudgingly had his administration come to the rescue of assaulted Freedom Riders in Alabama in May 1961. But unlike adminsitrations before them, they had come. Then, for their own political purposes, the President and his brother Robert, the attorney general, beseeched the civil rights movement’s student firebrands to stop fomenting unrest with their bus-borne Southern invasions. Instead, the Riders should focus on winning the right to vote, the Kennedys had counseled. But voter registration had proved just as incendiary as Freedom Riding. In Mississippi, a local farmer had been shot to death for it by no less than a member of the state legislature, who went not only unpunished but also un-arrested. Civil rights organizations were quick to commend the administration’s tentative steps in their direction. On December 26, at the threshold of 1962, Wyatt T. Walker of Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference nominated Robert Kennedy for American of the Year for the period just ending. He wrote that Kennedy’s Justice Department had shown “decisiveness” in dealing with the Ku Klux Klan riot against the Freedom Riders at the Montgomery, Alabama bus station and had sought a “new ruling with teeth” from the Interstate Commerce Commission to forcibly desegregate travel facilities in the South. Robert Kennedy had made it clear, Walker wrote, that “his department means business.” But Kennedy’s Justice Department had strong opposition in its own frontyard: the FBI. Its director, J. Edgar Hoover, was convinced that this conflagration of civil rights unrest was the work of Communists, as if illegally deprived Americans did not have the sense to resent their condition on their own. Hoover was preoccupied with domestic spying, focusing particularly on American black aspiration and its young patriarch, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. On January 8, Hoover informed Kennedy that New York lawyer Stanley Levison, a preeminent member of King’s inner circle, was a Communist. The implication was that King was, too. This attempt to vilify a black freedom movement was no aberration on the part of either the FBI or Hoover. Ever since its origination in 1908, the Bureau had been averse to involving itself in cases of injustice toward African Americans. Hoover himself was a staunch Northern ally of Southern oppressors of blacks. His FBI ignored virtually all cases involving racial injustice, hired only a tiny minority of blacks itself, and kept the few it did hire in such low-level jobs as drivers for Hoover. In fairness to Hoover, he had become the Bureau’s director in 1924, just seven years after the Marxist revolution in Russia. The Communist uprising alarmed not only the world’s autocrats but also its democracies, and in the 1930s the Great Depression saw many American intellectuals and other idealists turn toward Communist ideology as a solution to the spreading poverty, hunger, and misery. Hoover became certain that rising black discontent in America was a breeding ground for Communist revolt. It seemed not to occur to him that the best way to short-circuit such a possibility would be to extend to non-white Americans the rights the nation claimed to offer all its people. Martin Luther King Jr. became just the latest in a lengthy line of FBI surveillance targets. Hoover had been highly instrumental in establishing an evidential basis for the 1924 imprisonment and eventual deportation of Marcus Garvey, one of the most important early black leaders. By the 1960s, Hoover was gathering data on not only black leaders but also his own federal bosses. Robert Kennedy dismissed the Communist threat. He saw the U. S. Communist Party as a joke peopled with more FBI infiltrators than dedicated members. But he had a thorny problem with Hoover’s Bureau. Because of the demands of their jobs, its Southern agents had to be friendly with local police organizations, which in turn were directly or indirectly connected to local Klans. Justice Department secrets were hard to keep. And the fight for racial justice was complicated by divisions within itself. The Albany (Georgia) Movement, which had suffered such a resounding defeat in December with King’s seeming surrender after just a one-night jail stint, highlighted those fissures. The NAACP, a black establishment organization long devoted to challenging segregation in court rather than battling it in the street, competed with King’s more confrontational Southern Christian Leadership Conference. King’s SCLC meanwhile competed with, and tried to co-opt, the nonviolent but ultra-militant young Freedom Riders of SNCC and CORE. Yet the movement’s disparate elements, for all their balkiness, worked in the end toward the advancement of the whole. The Freedom Riders’ incursions, via buses and trains, into South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi had focused media attention on the ferocity of Southern racism. This in turn brought money and muscle to King’s SCLC, seen nationally as the organization mounting the broadest campaign against the problem. As 1962 opened, the whole machine was beginning to work. The New York office of the SCLC, under the direction of Stanley Levison, had begun to bring in vital funds through direct-mail solicitations. The Rev. Andrew Young’s effective solicitation of new Voter Education Project grants put more money behind the SCLC’s enfranchisement campaign. And the citizenship schools at Dorchester, Ga., headed on the ground by longtime South Carolina schoolteacher Septima Clark, daughter of a slave, backed the money with grassroots muscle bused in from local communities across the Deep South. But the Atlanta office of the SCLC was as laid-back as New York’s was efficient. In January, King moved to change that. Having to spend much of his time on the road generating support, he needed someone to apply New York-style efficiency to the voter registration effort. He asked Jack O’Dell, office manager of Levison’s New York operation, to begin commuting to Atlanta and dividing his time running the two offices. O’Dell became the organizer and supervisor of logistics behind the voter-registration projects, getting the necessary supplies to the front lines of the struggle. Diversity, one of the movement’s strengths, was sometimes a weakness, a wedge between factions. At Dorchester, Young was confronted with a problem involving a young white female volunteer, a Northern college student who assumed that the only way to fit in with poor African Americans in the South was to go without baths and wear grimy clothes; in reality, Young later wrote, the poor black people with whom he was acquainted “made a fetish of cleanliness,” ridding themselves of their labors’ dirt and sweat as quickly as possible. The young woman’s roommates at Dorchester complained to Young. He understood their problem but said he couldn’t get involved in a matter so sensitive. The roommates then took their problem to Septima Clark. Clark touched the young woman’s forehead and said she seemed to have a fever that a warm bath might help cure. On that premise, they got the young altruist into a bathtub, but the tactic proved only marginally effective. A roommate soon returned to Clark complaining that when the girl exited the tub, she got right back into those “same blue underpants.” One of the divisions, albeit unintentional, lay between Young and his underlings, and at first it was a gulf. Young hailed from the tiny black upper class in New Orleans, had graduated from Howard University in Washington, D.C., and had lived in a New York City apartment for four years working with the National Council of Churches. He was continually gone to points in the East and South in fundraising efforts. Most of the students and some of the teachers at the school were poor, the condition that Southern racism meant to keep them in. Most of the students had hardly been out of their counties, let alone their states. And their no-nonsense schoolmistress, Clark, mothered them fiercely. One Sunday, to attend opening ceremonies when a new busload of students arrived, Young flew in from New York by chartered plane. Hungry, he headed for the pantry, but Clark caught him. She told him the new class had ridden a bus all night to get there and its members were hungry, too; he should not eat unless he was willing to share with them. He told her there were no funds for a breakfast for everybody. She then reminded him of life on their lower level. They were humble people who would not aspire to attend the kind of churches Young frequented and preached in, because the congregations there were too well-dressed. But the new students’ eyes missed nothing. They would notice a reluctance to mingle with them, and they would notice other things, too–things which would discourage them from thinking they could aspire to the rights of white people if their own leaders would not recognize them as equals. If Young could use donated money to charter a plane, could he not spare two or three dollars each to buy these poor exhausted travelers a breakfast? Clark asked. Doing otherwise, she told him, was “not wise.” It was a point well taken, and she soon had him eating his lunch out of a sack in the company of class members. It was another small step down a long road. (For more information see Parting The Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1988; “Racial Matters”: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America, 1960-72 by Kenneth O’Reilly, The Free Press 1989; An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America by Andrew Young, Random House 1996; and The Children by David Halberstam, Random House 1998.) |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta