|

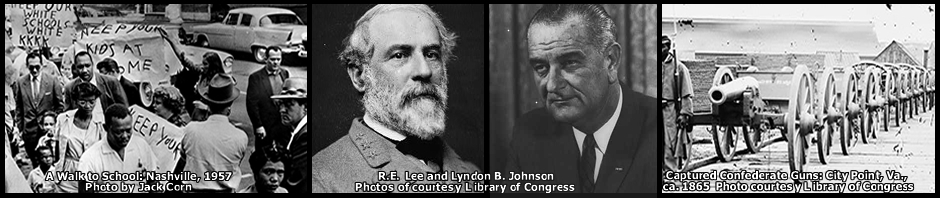

1865 The once-vaunted Confederate military, winnowed to dribs and drabs, now fell to pieces. On the month’s third day, at Waynesborough, Va., a unit of Union cavalry under Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer routed and destroyed most of the surviving portion of Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s Shenandoah Valley army, capturing nearly the total force, more than 1,000 men. Early and his staff managed to escape and head for Richmond. On Mar. 7, most of the remainder of the once-formidable Army of Tennessee, a mere remnant after the terrible battles of Franklin and Nashville, arrived in Kinston, N.C., to join Generals Joseph E. Johnston and Braxton Bragg. There they would try to help stop Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s Federals driving north from South Carolina. It was a forlorn hope and of little consequence. Generals of the greatest ability on both sides knew the outcome had been decided. Noncombatant politicians were apparently the remaining people most in favor of continuing to fight. On the night of Mar. 2, Confederate General Robert E. Lee and Lt. Gen. James Longstreet went to see President Jefferson Davis in an effort to end the carnage. In a recent meeting requested by Federal Maj. Gen. E. O. C. Ord to discuss prisoner exchange, Longstreet had been told that Ord thought his commander, Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant, would react favorably to a letter from Lee. Ord had suggested the letter seek a talk in which “old friends of the military service could get together and seek out ways to stop the flow of blood.” At the Confederate White House, Lee and Longstreet encountered Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, Davis’s new Secretary of War. As soon as Breckinridge arrived in Richmond and learned from Davis the dire condition of the armies, he had urged Davis to extend peace feelers. Breckinridge accompanied Lee and Longstreet as they entered Davis’s study. There the trio apparently tried to tell their President, without actually saying it, that the end was at hand. Lee told Davis he thought his 50,000 hungry men–of whom just 35,000 remained healthy enough to fight–could hold off Grant’s 120,000 in front of Petersburg for two more weeks. Then he would have to abandon Richmond and try to link up with General Johnston in North Carolina. That should have told any rational person that the drama was played out, but Davis by now was withdrawn and apparently semi-delusional. “The war came,” Davis had recently said, “and now it must go on till the last man of this generation falls in his tracks and his children seize his musket and fight our battle.” So he gave Lee permission to write to Grant, but doubtless with little hope that the letter could come to anything. Lee himself had little hope, too, mostly because of Davis. He told his President that he thought Grant “will consent to no terms unless coupled with the condition of our return to the Union.” He added a sentence that hardly recommended continuing to fight: “Whether this will be acceptable to our people yet awhile I cannot say.” But Lee went ahead and wrote Grant, mentioning what Ord had said and proposing that they get together to try to arrive “at a satisfactory adjustment of the present unhappy difficulties by means of a military convention.” On Mar. 4, Grant answered–after conferring with President Abraham Lincoln. Just as Lee had predicted, Grant said the only major matter on which he was authorized to meet with Lee was to accept the surrender of Lee’s army.

*

That same day, Mar. 4, Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated for the second time. His speech, like his great Gettysburg Address of 1863, was short and as poetic as a passage of Scripture. Its most quoted words are the soaring and remarkably forgiving ones at its end–“With malice toward none, with charity for all…”–but in the middle there was another one referring to the war itself. In it, the U. S. President sounded as determined to carry the fight to the last ditch as did Jefferson Davis in Richmond: “…if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword–as was said three thousand years ago, so it still must be said, ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’” The Confederate South’s very foundation, slavery, was becoming history–in name, anyway. On Mar. 3, the U.S. Congress passed a law creating the Freedmen’s Bureau to aid former slaves displaced by the war and in need of sustenance and employment. On Mar. 9, Vermont became the ninth state to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment outlawing slavery. Nobody seemed to notice, though, that this proposed addition to the Constitution had no teeth to punish anyone who continued to hold persons in bondage. Formal slavery was losing its grip even in the Confederacy. On Mar. 13, far too late to be of any use, the Confederate Congress sent President Davis a bill authorizing the arming of slaves to fight in the Confederate armies. The measure left to the individual states the matter of whether these black Confederates would be given freedom. Davis signed the bill into law and castigated the lawmakers for delaying passage of the measure. On Mar. 23, Abraham Lincoln left Washington for Virginia to get away from the worries of Washington. He would confer with Grant and other Union generals at the front.

*

Meanwhile, Grant’s army in Virginia and Sherman’s in North Carolina got stronger. On Mar. 11 Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan’s Shenandoah Valley cavalry, having destroyed Early’s tiny army, now came east to add to Grant’s strength. Since the 7th, Federals under Maj. Gen. Jacob Cox had been working to repair the railroad from New Berne to Goldsborough, N.C., to get supplies to Sherman from the Atlantic coast with the greatest dispatch. On the 11th, Sherman reached Fayetteville, where he had his troops destroy everything that could be of use to the Confederacy. On Mar. 15 he headed for Goldsborough in three columns. Jacob Cox’s troops, finishing their railroad repair, also headed for Goldsborough to link up with Sherman. On St. Patrick’s Day, Mar. 17, another 45,000 Federal troops under Maj. Gen. Edward R. Canby prepared to capture well-fortified Mobile, Ala., which was garrisoned by some 10,000 Confederates. On Mar. 18, Confederate cavalry under Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton assailed the leftmost of Sherman’s three columns, hoping to slow Sherman while Johnston solidified a position at Bentonville, N.C. The next day, Hampton withdrew while fighting–until Johnston attacked the Federal column of 30,000 with his whole 20,000-man army, forcing the Union force to pull back and fortify. Johnston had hoped to vanquish the 30,000 Federals before the others could come to their aid, but he failed. Sherman’s other two columns turned back toward Johnston, arriving at Bentonville on Mar. 20. Then Johnston and his 20,000 faced 100,000 Federals. The fighting continued on Mar. 21, with Johnston parrying Sherman’s moves. This and the previous two days of fighting constituted the last realistic Confederate attempt to stop Sherman. In it, Johnston lost 2,606 men compared to 1,646 for the Federals. Meanwhile, Federal cavalry launched two raids farther south to aid Sherman. On Mar. 20 Maj. Gen. George Stoneman left Jonesboro, Tenn., with 4,000 troopers bound for western North Carolina. On Mar. 22, Union Maj. Gen. James Harrison Wilson inaugurated a much larger incursion. Wilson led 14,000 horsemen into the very bowels of what remained of the Confederacy’s infrastructure. He meant to destroy the military capacity of Selma, Ala., one of Dixie’s last major munition-making centers, and then aid Canby against Mobile. Wilson divided his force into three columns to confuse his skeletal opposition, composed mainly of Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s 2,500 cavalrymen. Wilson skirmished with Confederates at Houston, Ala., on Mar. 25, Black Warrior River on the 26th, Jasper on the 27th, and Elyton (now Birmingham) on the 28th. On the 31st, as Forrest struggled to gather some 6,000 widely-separated Confederates, Wilson scattered and routed some 2,000 of them as he and his comparative horde drove hard past Montevallo toward Selma.

* Back at Petersburg, Lee made one last desperate attack. On Mar. 25, he sent Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon in a furious assault on so-called Fort Stedman on the Federal right. Lee’s hope was to force Grant to contract his left to protect his right, which guarded his supply line northward. That might open a westward route through which Lee could get away and march southward to Johnston in North Carolina. Gordon’s 4 a.m. attack broke through the Union line and captured Fort Stedman, but a 7:30 a.m. Federal counterattack overwhelmed the Confederates. Lee ordered a withdrawal, but too late to save another precious 1,900 men who were captured. Total Confederate casualties numbered 4,000, compared to barely more than a thousand Federal ones. On Mar. 29, Grant–instead of contracting his left–extended it farther by sending Sheridan’s cavalry, newly arrived from the Shenandoah Valley, around Lee’s right. Rains slowed Sheridan, though, and Lee dispatched Maj. Gen. George Pickett, of the famous doomed charge at Gettysburg, to oppose him. On the 31st, with the end of the rains, the Union horsemen got going again, only to be stopped by the Confederates. But Pickett was vastly outnumbered, and he withdrew. His retreat left Lee no option but to try to flee Petersburg, abandon the Confederate capital at Richmond, and outrun Grant southward to North Carolina.

[For more see The Civil War Almanac by John S. Bowman, exec. ed., Bison Books 1982; Jefferson Davis: The Man and His Hour by William C. Davis, HarperCollins 1991; Lee by Clifford Dowdey, Little Brown 1965; Lincoln by David Herbert Donald, Simon & Schuster 1995; and The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001.] |

1965 Great opportunities are rare and fleeting. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. sensed a golden one during the first week of March in Selma, Ala. King had returned to the old Alabama town on Mar. 1 and first toured its rural outback, rife with thickets that could hide an assassin. He had dared such dangers since 1955. Then, as a new Montgomery pastor, he led the bus boycott resulting when seamstress Rosa Parks disobeyed a driver’s order to surrender her seat to a white man. Selma in ’65 was at least as dangerous as Montgomery in ’55. Its outlying counties were likely more so, bristling with rifles and sinister Ku Kluxers. This day, with King present, was especially explosive. It was also the month’s first Monday, one of just two March days on which Alabama law allowed citizens to apply to register to vote. Today was rainy, and King led soaked black Selmans on marches to and from the courthouse. There an unprecedented 266 managed to make application, but how many, if any, would be accepted nobody knew. At day’s end King had to speed back to the Montgomery airport to go to Washington for a scheduled address at Howard University. In Selma, maverick aide James Bevel urged black Selmans toward an unauthorized idea which he and his wife, Diane Nash, had brainstormed after the Birmingham church bombing that had killed four schoolgirls in 1963: to march on the state capitol at Montgomery and demand black rights. Arriving back in the Selma area on Wednesday, King proceeded to Marion, seat of his wife’s home county of Perry. His mission there was to eulogize a 26-year-old local demonstrator, Jimmie Lee Jackson, who had been shot to death by a state highway patrolman in late February. Three miles to a cemetery in the rain, King led 1,000 mourners. The large number of black people ready to be seen identifying with Jackson likely influenced King. He decided now to go ahead with a Selma-to-Montgomery march–even though the trek’s midpoint would be on narrowed highway in rural and especially dangerous Lowndes County, which was so racist that its stores refused to sell Marlboro cigarettes and Falstaff beer because the parent companies were said to have supported the NAACP. King slated the 54-mile march for Sunday, Mar. 7, and left town again on his whirlwind speaking schedule. On Mar. 6, Alabama Gov. George Wallace forbade the march. King, still out of town, preached at his home church in Atlanta on the 7th and thus was unable to return to Selma in time to lead the march. As black volunteers from surrounding counties gathered early on the 7th, the crackling of a police radio in the courthouse was monitored by female deputies wearing Confederate flag pins: “There’s three more cars of niggers crossing the bridge. Some white bastards riding with them.” The trek departed without King at 2:18 p.m. from a black Selma church called Brown Chapel. Some 525 marchers were followed by two ambulances, three borrowed hearses carrying supplies and doctors, and a flatbed truck bearing four porta-potties. Police quickly stopped the trailing vehicles. They declared the highway closed to all but foot traffic–and barred the doctors, who were movement sympathizers from out of town, because they were unlicensed by the State of Alabama. A little farther on, two hundred feet past Edmund Pettus Bridge over the Alabama River, a line of heavily armed lawmen halted the marchers and ordered them back to Selma. They refused to go. Suddenly, state and local officers–plus deputized civilians, some on horses–charged the procession, discharging tear gas canisters and striking demonstrators’ skulls with billy clubs. A tear-gas cloud shrouded screaming marchers as they turned to run back to Brown Chapel. The police followed with whips, pistols, tear gas, and clubs. Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee chairman John Lewis, at 25 an oft-beaten veteran of the movement, had been a lead marcher, and he suffered a fractured skull in the melee. But back at the church, before being taken to a Catholic hospital that was the only one in Selma treating blacks, he gave a short, outraged speech to weeping marchers taking refuge in the sanctuary. “I don’t see how President Johnson can send troops to Vietnam–I don’t see how he can send troops to the Congo–I don’t see how he can send troops to Africa and can’t send troops to Selma, Ala.,” he cried. “Next time we march we may have to keep going when we get to Montgomery. We may have to go on to Washington!” Mar. 7 became known thereafter as Bloody Sunday. It was not hyperbole. * The next few days were blurred by controversy and laced with some backdoor federal betrayal of King and the marchers. Ultra-bigoted FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover–whose agents arrested only three white men in Selma, and these for beating an agent they mistook for a reporter–forbade his men from warning King of two new death threats in Selma. Meanwhile King regretted not being in Selma on Bloody Sunday. He had tried in vain to get the march rescheduled for Monday so he could. Now he addressed 1,000 people in Brown Chapel after wiring Northern churchmen to join him in a Tuesday “Ministers’ March to Montgomery.” Predictable problems arose. On Tuesday, Mar. 9, a federal judge signed a court order prohibiting another march. Diane Nash bitterly reviled the federal government as the enemy while 800 Protestants and Catholics, black and white, hurried in from 22 states. King publicly considered defying the court order. Saying he “would rather die on the highways of Alabama than make a butchery of my conscience,” he led the Tuesday marchers to Pettus Bridge. Again, lawmen were drawn up on the structure’s other side. But after the marchers knelt in prayer, the police suddenly pulled back, opening the highway to the marchers. It looked like an invitation to a trap, an ambush on narrowed road in the lonely wilds of Lowndes County. King now rethought making an outright foe of the federal court by offering up the marchers and himself for massacre in Lowndes County. He ordered everybody back to Brown Chapel. Among the marchers, there was simultaneous relief and anger at King. SNCC officer James Forman was so openly contemptuous of King’s Tuesday action, or inaction, that on Wednesday he vowed to “radicalize” the movement by opening a rival SNCC campaign in Montgomery. But danger enough lurked in Selma. Tuesday evening, Unitarian minister–and marcher–James Reeb emerged from a local eatery to have his skull cracked with a baseball bat by an ambusher who hit him from behind. Reeb was hospitalized near death. The next day, Mar. 11, he died. That day, the White House and the Justice Department asked for an FBI escort in Alabama to safeguard Mrs. Reeb and were turned down. Meanwhile, J. Edgar Hoover quietly removed from Selma the agent who had identified individual local officers who violated federal law at the Pettus Bridge on Mar. 7. On Friday, Alabama Gov. Wallace asked for a meeting with President Johnson and got it. The next day he railed to the President about how blacks “trained in Moscow and New York” couldn’t be satisfied–wanting front seats on buses, then to take over public parks, then public schools. After that, Wallace complained, they wanted jobs and then distribution of wealth without work. Johnson alternately schmoozed and berated the governor. “Don’t you shit me, George Wallace,” he said at one point and advised Wallace to forget 1865 and think about 2065. “When the President works on you, there’s not a lot you can do,” Wallace moaned to aides on his flight back to Alabama. Meanwhile another plane, a small one labeled “Confederate Air Force,” dropped leaflets on Selma calling for all local demonstrators to be fired from their jobs and advocating a defense fund for the arrested alleged murderers of Rev. Reeb. On Monday, Mar. 15, Johnson spoke to a joint session of Congress. King, although invited, decided to stay in Selma to eulogize Reeb. Johnson, too, paid tribute to the slain minister in his address, saying: “We thank God for the life of James Reeb. We thank God for his goodness.” The President went on to assert that no matter how many victories America won on how many different fields, if it continued to treat black people unequally “we will have failed as a people.” He then said that “all of us must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.” Civil rights advocates were dumbfounded and overjoyed to hear Johnson’s Texas drawl then raise the movement’s best-known rallying cry: “And…we…shall…overcome!” * On Mar. 16, a fortyish Detroit mother of five named Viola Liuzzo, daughter of a Tennessee coal miner and wife of a member of the Teamsters Union, got out of bed so inspired by the President’s speech the night before that she headed for Selma alone in her Oldsmobile. That same day in Montgomery, police waded into 600 Jackson State University students led by James Forman seeking to present a voters’ rights petition to Gov. Wallace. The officers beat them into a bloody retreat. On Sunday, Mar. 21, on its third try, the vaunted march from Selma to Montgomery set out across Edmund Pettus Bridge around 1 p.m.–escorted by 19 Army jeeps, four Army trucks, two helicopters overhead, and the 31st Infantry Division of the federalized Alabama National Guard. The trek’s logistics were daunting. The federal judge’s order allowed only 300 marchers on the narrowed road through Lowndes County, so the surplus marchers before and after Lowndes had to be transported back to Selma or forward to Montgomery. A special train and volunteered automobiles were designated for this task. Viola Liuzzo’s Oldsmobile was one of the latter. Enduring a long hard rain and 22 miles of Lowndes County, the march entered Autauga County, where the highway widened to four lanes and the number of marchers more than doubled almost instantly. The number kept proliferating. By the time they reached the Montgomery outskirts they numbered more than 10,000, some estimated. The crowd was so large that it jostled diminutive Rosa Parks out of the procession and onto a curb before others recognized her and gave her a new place in line. It took more than an hour and a half before the final marchers passed the starting point four miles from the state capitol. At the capitol on Thursday, Mar. 25, Gov. Wallace peeked through drawn blinds at the gathering horde. He had had aides cover with plywood the bronze floor emblem memorializing the spot where Jefferson Davis had taken his oath as president of the Confederate States of America. On the steps outside, blonde Mary Travers of the Peter, Paul and Mary folk-singing trio kissed singer/activist Harry Belafonte on the cheek, an act whose camera-captured image soon scandalized many white Southerners. Among many speakers, Rosa Parks told how as a child she had hidden from Klansmen and how her family had had their land taken from them. Then Martin Luther King Jr. stepped up to say such horrors were on the way out in Alabama. King said the “often bloody trail” of their quest for civil rights had become “a highway up from darkness.” Alabama’s segregation, he said, was on its deathbed. “The only question,” he added, “is how costly the segregationists and Wallace will make its funeral.” * With the great trek completed, marchers had to get home. Once again, Viola Liuzzo’s was one of many cars volunteered for the job. Liuzzo, who had been a marcher herself, now took over her steering wheel. She had been informed that its current driver, Leroy Moton, 19, might not have a license, so she tactfully told Moton she wanted to practice for the long drive back to Detroit. Moton moved to the front passenger seat, and they dropped one rider at the Montgomery airport and headed for Selma carrying a black man from Selma and three white women from Pennsylvania. They were tailgated for a while by two cars with flashing lights, but they successfully reached Brown Chapel, unloaded, and started back to Montgomery for more. On the narrowed road in Lowndes County, a car carrying four Ku Klux Klansmen from Birmingham pulled alongside them. Three pistols shot Mrs. Liuzzo in the head, killing her instantly and showering young Moton with blood and window-glass. He played dead, then ran into the night and eventually flagged down a ride into Montgomery. Mrs. Liuzzo had hardly died before J. Edgar Hoover besmirched her name to President Johnson. He implied that Liuzzo and Moton were sexually involved–they weren’t at all–and that she had a doper’s needle marks on her arm. The marks turned out to be cuts made by the bullet-shattered glass, and a medical exam found no drugs in her system. Hoover instantly had a lot of information, factual and otherwise, on the shooting. That was because he had an informant in the shooters’ car. The man had been participating in Klan violence against civil rights for five years. Hoover also tried to run down the reputation of Liuzzo’s husband to the President. The FBI director caused Johnson to wait so many hours to call the husband in Detroit that Mr. Liuzzo, up all night seeking information on his wife’s murder, had finally gone to bed. The family told the White House they didn’t think their father should be disturbed. On Monday night, Mar. 29, Viola Liuzzo’s Detroit funeral drew 1,500 mourners. They stood and cheered James Leatherer, a one-legged settlement house worker from Saginaw who had participated in the Selma march. Leatherer told the crowd that Liuzzo’s death was a message to still-undecided Americans: “you have to get off the fence.” * The next day, Mar. 30, J. Edgar Hoover finally took a long-deserved hit from the rear. President Johnson had been repelled by information obviously obtained by FBI spying on a journalist friend of long standing, closet homosexual Joseph Alsop. To a lesser extent, Johnson was also concerned about government spying on King. The President instructed Atty. Gen. Nicholas Katzenbach to order Hoover to stop all microphone surveillance and to submit requests for all wiretap activity for approval by Katzenbach, who himself had been uncomfortable with Hoover’s activities. Hoover, who had all but coerced his authority to wiretap from prior Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy, now saw his strongest power source severely threatened. One of the sorriest chapters in U.S. law enforcement history was nearing its end. [For more, see At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years 1965-68 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 2006; Reporting Civil Rights, Part Two by Clayborne Carson, David Garrow, Bill Kovach, and Carol Polsgrove, eds., Library of America 2003; Walking With The Wind: A Memoir of the Movement by John Lewis and Michael D’Orso, Simon & Schuster 1998; and An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America by Andrew Young, HarperCollins 1996.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta