|

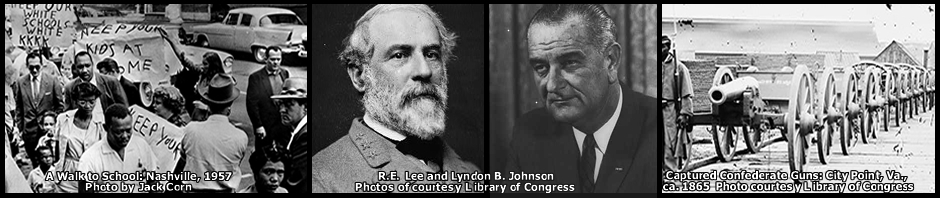

1863 November opened with all eyes on Chattanooga. The little Tennessee city was critical. Surrounded by mountains and additionally guarded on its northern and western sides by a long curl of the Tennessee River, it commanded an east-west rail route as well as the most direct one from Virginia to Deep Dixie. The Confederates’ September victory in the Battle of Chickamauga in north Georgia had chased the Federals back into the city, where they sat starving and besieged by General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Bragg thought his mountain position impregnable. On Nov. 4, at the behest of President Jefferson Davis, Bragg ordered the corps of his most respected subordinate, James Longstreet, 100 miles northeast to Knoxville, which had been captured in September by Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Ohio. As Davis and Bragg both knew and wanted, Longstreet’s departure removed one of Bragg’s critics, who had become legion. Bragg and Davis also thought that threat of a Longstreet attack would stop any Union attempt to reinforce Chattanooga from Knoxville. It might even induce the Federals to detach some of their forces northward. The latter proved a vain hope. Chattanooga’s new Union commander, Fort Donelson and Vicksburg victor U. S. Grant, chose not to divide his men. He had just opened a more efficient supply line to Bridgeport, Ala., and was intent on building up, rather than dispersing, his numbers. Refusing to accept the impregnability of the Confederate-held mountains, he meant to attack Bragg as soon as possible. On Nov. 12, Longstreet and 15,000 men–his 10,000 infantry plus 5,000 cavalrymen under Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler–reached Loudon, west of Knoxville, and readied an attack. On the 14th, Longstreet tried to intercept Federal troops withdrawing into Knoxville but failed in a battle at Campbell’s Station, southwest of the town. The Confederates suffered 174 casualties, the Federals more than 300. On Nov. 15 well to the southwest, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman and nearly 20,000 Federals marching from the Mississippi River arrived at Bridgeport, Ala. Thus in both Chattanooga and Knoxville, events were moving toward settling the question of who would control East Tennessee. * * * Events proceeded elsewhere. On Nov. 2, President Lincoln received an invitation to speak a few brief, appropriate words at Gettysburg on Nov. 19. His remarks, if he consented to make them, would be part of battlefield consecration ceremonies featuring a two-hour address by Edward Everett, who was a former secretary of state, U. S. senator, and president of Harvard. Lincoln, seeking stages on which to emphasize that the North’s goal was nothing less than survival of democracy itself, accepted the invitation. Meanwhile, in Virginia on Nov. 7, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac attacked Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia on the south bank of the Rappahannock River. In the fray, the Confederates lost 2,000 men killed or captured. In South Carolina, Fort Sumter was becoming little more than heaps of dirt and brick after prolonged Union shelling. It received another 1,700 artillery rounds between Nov. 7 and Nov. 10, killing no one but further damaging the fort. On Nov. 9, President Lincoln found evening diversion in one of his favorite pastimes: attending the theater. The play this night was titled The Marble Heart. The star performer was a brilliant and wildly dramatic young actor named John Wilkes Booth. Eight days later, the President began writing the little speech he was to give at Gettysburg. He spent much time on it, using ideas he had pondered over the preceding weeks. On Nov. 18, he and a party including Secretary of State William Seward boarded a train for Gettysburg, and the next day, following ceremonies that included Everett’s extended oration, Lincoln delivered his attempt at brief, relevant words. There were only 272 of them in his talk, and most of the people present missed them. When he sat down, they were still settling in for one of the longer addresses they were accustomed to endure from politicians. Lincoln thought his effort had misfired–until newspaper reviews came in. Notable among them was that of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican, which described the “little speech” as “deep in feeling, compact in thought and expression, and tasteful and elegant in every word and comma.” History has concurred, placing it among the handful of greatest speeches made by an American. * * * The attack plans of both Grant at Chattanooga and Longstreet at Knoxville were delayed. Each had initially intended to make his move around Nov. 20. Grant’s problem was heavy rains that slowed the march of Sherman’s troops into their assigned position in Chattanooga. Sherman’s men had to reach the Federal left from Bridgeport, Ala., which was miles beyond the Union right. Longstreet, meanwhile, postponed his assault because he wanted to confer with an engineer on how to take a powerful redoubt, Fort Sanders, in the Federal defenses around Knoxville. While he waited for Sherman on Nov. 21, Grant perfected his plan. Under it, Sherman would take the northern end of Missionary Ridge on the Federal left, after which “Fighting Joe” Hooker would create a diversion toward Lookout Mountain on the right. Then, with the Confederates preoccupied with their two wings, George Thomas would strike the Federal center in the main attack. On Nov. 22, incessantly pestered from Washington about the welfare of Burnside and worrying that Bragg might suddenly take more of his troops to Knoxville to aid Longstreet, Grant instructed Thomas to make a demonstration against the Confederate center the next day to see if Bragg was still in place. Eager Union troops didn’t just demonstrate. They took Orchard Knob, a hundred-foot-high hill facing Missionary Ridge, and asked what to do with it. Grant told them to hold it. He moved his headquarters there for the main battle scheduled for Nov. 24. Early on the 24th, Sherman crossed the Tennessee River north of Chattanooga and headed for the upper end of Missionary Ridge. At the same time, Hooker began his ordered demonstration against Lookout Mountain on the line’s other end. Hooker, though, did not intend to demonstrate. He ordered his men to take Lookout. As the day progressed, Hooker’s men–only lightly opposed by Confederates–made their way to just below the crest of the mountain. Sherman, meanwhile, moved lethargically against the north end of Missionary Ridge, repeatedly entrenching and eventually finding that the hill he thought was the ridge’s north end was separated from it by a deep ravine. Grant seems to have wanted to give the glory job to Sherman this day, but Sherman was not up to it. He remained haunted by the death of his favorite son several weeks earlier. He had allowed nine-year-old Willie Sherman to come to visit the theater of war, and the boy had died of typhoid fever. Sherman, always excitable and never notably stable, wrote his wife that “everywhere I see poor little Willie.” So Sherman made poor progress, while Hooker all but took Lookout Mountain. In fact, the next morning Hooker’s men found that the Confederates had abandoned the crest and gone down the other side in the night. For many hours on the 25th, Grant waited to hear of the progress of Sherman before loosing Thomas’s 19,000 men on the center. The plan was for Thomas to join in after Sherman attacked on the left. There was no word of a Sherman attack, though, and Thomas wanted to wait until Hooker’s men could descend Lookout and join his right in the attack on Missionary Ridge. Grant had to repeatedly order an advance to the foot of the ridge before Thomas finally moved his men–but when they did move they didn’t stop at the foot. With Confederates firing down on them from above, they had to sweep on up the ridge to keep from being killed or wounded at the bottom. They were aided by the fact that Bragg had placed his men in three lines on the ridge–one at the bottom, one in the middle, and one at the top. When those at the foot turned to flee the Federal attack, they interfered with the fire of their comrades above. And the angle of ascent was so steep that Confederate cannon on the crest could not be depressed low enough to target them. To the amazement of Grant and Thomas, to say nothing of Bragg, they charged all the way up the ridge and ran the Confederates off it. It was a stunning victory won by the Union’s riflemen, not their commanders. The next day, Nov. 26, Longstreet began planning his assault on Fort Sanders at Knoxville. He launched it disastrously three days later in cold, wet weather. Preliminary reconnaissance had not detected a deep ditch in front, and the Confederate attackers had no ladders with which to climb out of the ditch and up the walls of the fort. Longstreet had neglected even to soften up the position with an artillery shelling. November thus became a Confederate disaster. At Chattanooga and Knoxville, the Federals had lost 5,800 and fewer than 700 men respectively, while the South had lost 6,800 and 1,300. On the month’s final day, the South suffered another loss, but one largely un-mourned. On that date, President Davis accepted the resignation of Braxton Bragg. All but to a man, his army applauded.

[For more, see The Civil War Almanac by John S. Boatner, Bison Books 1982; The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001; Lincoln by David Herbert Donald, Simon & Schuster 1995; Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War by Patricia L. Faust, ed., Historical Times Inc. 1986; The Shipwreck of Their Hopes by Peter Cozzens, University of Illinois Press 1994; Sherman: Fighting Prophet by Lloyd Lewis, Harcourt Brace 1932; and The Knoxville Campaign: Longstreet and Burnside in East Tennessee by Earl J. Hess, LSU Press 2013.) |

1963 The climate of raging discontent in 1960s America reached a flashpoint in November. Before the end of the month it had exploded into national horror. The lead-up featured more of the ever-tightening fist of J. Edgar Hoover’s paranoid FBI, coupled with quailing by an Administration made servile to Hoover by its President’s personal indiscretions. Now more than ever, the Hoover tail wagged the Kennedy dog in civil rights. On Nov. 1, Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy finally got around to answering a sensitive, three-month-old letter from Sen. Richard Russell of Georgia on the subject. Having to do with Hoover’s claim of Communist influences allegedly motivating Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the Russell letter had relayed to Robert Kennedy a constituent’s question as to whether King himself was a Communist. The Attorney General’s brother, the President, tried to craft a reply. His preferred response was that the FBI had cleared King of overt wrongdoing, but Hoover refused to sign off on that. The President then, in frustration, had the Attorney General send his deputy, Nicholas Katzenbach, to handle the matter in person. Katzenbach was surprised to find Russell tractable. The senator said he had just wanted a speedier answer to his letter, as any senator could expect. He said that as a longtime observer of African American preachers like King, he knew the man was no Communist. Russell, a member of Georgia’s upper class, then told Katzenbach that although he and the Administration were “a mile apart” on civil rights, he was “a hundred miles” from the position of anti-Communist racist howlers such as Alabama Gov. George Wallace. Meanwhile, a new and formidable voice on the American civil rights scene was emerging as a black “bad cop” to King’s “good” one. On Nov. 5, Malcolm X of the Nation of Islam stunned a student crowd at the City College of New York by attacking the hypocrisy of American democracy itself, the same democracy that President Kennedy so glorified in internationally-focused speeches. Democracy’s adherents had “sold us” from plantation to plantation “like cotton and cows,” Malcolm X said. They had “lynched black people from one end of this country to another.” In a ringing crescendo, he summed it up: “All the hell our people ever caught in this country, they have caught in the name of democracy.” But Deep Dixie seemed only more determined to make them keep catching it. On the same day Malcolm X spoke in New York, Democrat Paul Johnson was elected governor of Mississippi by an unusually close and historically precursory margin. Reubel Phillips, a former Democrat running as a Republican, had shouted that only the Republicans could save the state from the race-mixing Kennedy Democrats. In a state where no Republican had even tried to run for the governorship in 16 years, Phillips grabbed more than 40 percent of the vote. Which, of course, was almost totally Caucasian. * * * A week-long workshop to try to change that voter makeup began in Greenville, Miss., on Nov. 11. Its sponsor was the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and its moderator was Myles Horton, head of the infamously-progressive Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. The primary topic was whether to broaden the organization’s voter registration project, called Freedom Vote, by bringing in as many as 2,000 white students mostly from the North to enlarge the effort’s reach. The aim was to stage another mock vote alongside the regular 1964 election to show how many African Americans would have voted if the Mississippi establishment had let them register. But the idea of using white Northerners to help in the canvass proved unpopular. Many seasoned civil rights workers regarded white students from the North as snooty and naïve and so unused to bi-racial contact that in ultra-perilous Mississippi they risked the lives of themselves and co-workers. A workshop straw vote on Friday, Nov. 15, opposed having any summer project using white workers. The next day, sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer, who had become locally famous by virtue of her savage jailhouse beating a few months earlier in Winona, Miss., argued to the contrary. “If we’re trying to break down the barrier of segregation,” Hamer reasoned, “we can’t segregate ourselves.” Fabled civil rights hero Bob Moses joined Hamer, saying that “the one thing we can do for the country that no one else can do is to be above the race issue.” Moses engineered a second straw vote which put the summer project back on the schedule, but the workshop deferred further talk about white workers. * * * Meanwhile, J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI continued its campaign tarring King with the brush of treason. On Nov. 20, the FBI surreptitiously photographed King meeting with his lawyer, Clarence Jones, and firm friend Stanley Levison, the longtime advisor whom Hoover was insistently and falsely characterizing as a willing tool of Moscow. The photograph was made at the Intercontinental Hotel on a King trip to New York, where he appeared with Polish Jewish rabbi Abraham Heschel of Chicago at the United Synagogue of America. The brief meeting had to do with Levison’s longstanding help on a book King was working on. To Hoover, what the meeting was about obviously meant nothing. He cared only that King–at the Kennedy Administration’s iron insistence–had promised to stop seeing or talking with Levison because of the political sensitivity of Levison’s name. Six new FBI wiretaps on King had allowed FBI agents to learn beforehand of the brief hotel meeting, and Hoover soon sent the picture on to Robert Kennedy as if it was as important as a new shot of Cuban missile silos. Hoover’s headquarters hyped the photograph as a feather in the FBI’s cap. Hoover planned to use it as possible evidence in a trial–presumably of Levison–on charges of spying, and he preened over the Bureau’s ability to procure it under “trying circumstances” of weather and security. Hoover neglected to mention that the purportedly sinister trio’s business was nothing but a book manuscript. * * * By the day Hoover’s message went to Robert Kennedy, though–Nov. 25–the younger brother of the President had become the younger brother of an ex-President. On Nov. 22, John F. Kennedy had been assassinated in Dallas, Tex., in a bloody spectacle that shook Americans to their bones. African Americans mourned the slain Chief Executive as much as, and maybe more than, many other groups of citizens. Although he had continually tried to give their freedom goals a back seat to his political ones, they seemed to see the forward-looking thrust of his Administration as closer to their aims than those of his detractors. His Southern critics, after all, had pilloried him for being their friend. For the next two days, the country plunged into vales of grief and mourning. Its citizens seemed transfixed by non-stop images on television, which brought the horror into their living rooms to a degree never experienced in earlier political tragedies. They gaped at a stately funeral parade to Arlington National Cemetery, where the martyred President was laid to rest. The man who now took the national reins was vastly different from his predecessor. Unlike the Massachusetts heir to a fabulous fortune, Lyndon Johnson was a poor boy from Texas who had scrambled up from the opposite end of American society. With a willingness to twist arms and a genius for making deals, Johnson had leapt from schoolteacher to congressional aide to congressman to senator to Senate majority leader before becoming Kennedy’s vice presidential nominee, only added to the ticket to win Kennedy the South. Johnson had been seen as a traditional Southerner in the racial sense, but he wasn’t one, and as an unappreciated Kennedy appendage he had begun returning to the Rooseveltian progressivism he had displayed in his earliest political days. The day after the presidential funeral, Nov. 25–the same day Hoover crowed to the Justice Department over his photograph of King, Levison, and Jones–Johnson included King in a long list of appreciative phone calls to national leaders. The new President thanked the civil rights leader for his pleas for racial calm in the assassination’s wake. * * * But at a Thanksgiving Day service back in Atlanta on Nov. 28, King did not eulogize the dead president. Rather, he preached on the African-American history of captivity and said his congregants should not be fooled by Caucasian descriptions of it. “They try to romanticize slavery with all the magnolia trees and what have you,” he said, evoking laughs. He described how Africans were brought to America in chains under the “rawhide whip of the overseer,” with only “songs to give them consolation.” In remarks made the same day, Malcolm X put even more distance between himself and the late President. He said that the assassinated Chief Executive had been no more than a “fox” compared with the “wolf” that was George Wallace. To blacks, he said, Kennedy had been a “prison warden,” not a deliverer. [For more see Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-65 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1998; Walking With the Wind by John Lewis and Michael D’Orso, Simon & Schuster 1999; The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power by Robert Caro, Knopf 2012; and The Glory and the Dream: A Narrative History of America 1932-1972 by William Manchester, Little Brown 1974.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta