|

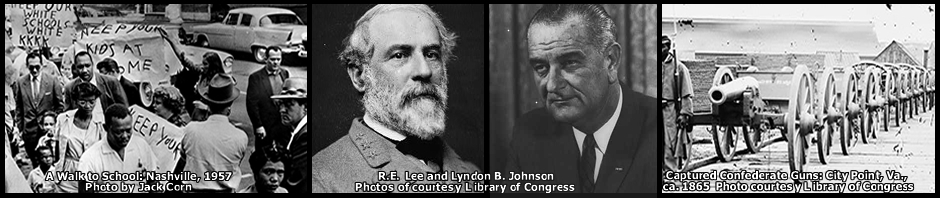

1863 The war’s two primary eastern armies blundered into battle on July 1 around the southeastern Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. From Robert E. Lee’s Confederates, a division in the corps of A. P. Hill headed there first on the report that the place contained some badly-needed shoes. When Hill’s men arrived just north of the little college town, however, they ran into two brigades of Union cavalry armed with new Spencer repeating carbines. These outnumbered Federals held off the Confederates until a Union infantry division arrived. The commander of the oncoming division, John F. Reynolds, had a few days earlier spurned President Lincoln’s offer of command of the Army of the Potomac, in which he would have replaced “Fighting Joe” Hooker. Reynolds declined out of apparent fear that he would not have a free hand. Now here at Gettysburg on this July 1 morning, Reynolds died, shot through the back of the neck by a Confederate sharpshooter as he turned toward the rear to direct placement of his troops. A division of Germans under Union Maj. Gen. O. O. Howard arrived on the field north of town just before more Confederates under Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell got there. Ewell attacked Howard front and flank, and the Federal line gave way with heavy loss. The survivors fled through Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill, a half-mile south of town. Lee had not intended to fight here, but he changed his mind. The developing battle appeared to fit a plan he had disclosed to a subordinate in late June. When he learned that the Army of the Potomac had left Virginia and was coming north to oppose him in Pennsylvania, he reportedly told division commander Isaac Trimble: “I shall throw an overwhelming force on their advance, crush it, follow up the success, drive one corps back on another, and…create a panic and virtually destroy the [Union] army.” That, Lee said, would end the war and assure Northern recognition of the Confederacy’s right to exist. But the 56-year-old Confederate commander, who had begun suffering heart problems in the spring, made an opening error. His gentlemanly order to Ewell to press ahead and attack Cemetery Hill “if practicable” seemed to leave Ewell the option not to, and he didn’t. That cost the Confederates a chance to cheaply acquire the battlefield’s high ground, some of which was not yet even occupied. The Southerners might thus have won the battle before the rest of the Army of the Potomac–and its new commander, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade–reached the field. Lee tried to recover momentum on July 2. The fighting was savage as the Confederates sought to wrest the hills from Meade’s embattled Federals. But Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, whose counsel of a more defensive strategy had been rejected, moved too slowly and did not adapt Lee’s orders to conditions on the ground. Although the Southerners pushed Meade’s left backward, their late and sometimes ill-directed assaults could not move the desperate defenders of Big and Little Round Top on the Northern left, Cemetery Hill in the center, and Culp’s Hill on the Federal right. Whole divisions on both sides were decimated in the day-long maelstrom of cannon balls and bullets. Lee believed the tattered heroes of his army could do anything, and he acted on that belief disastrously on July 3. After 140 cannon fired shells at the Federal lines for two earsplitting hours, he ordered the reluctant Longstreet to throw 11 brigades–some 14,000 men led by the division of Maj. Gen. George Pickett–across three-quarters of a mile of open field into the mouths of Federal artillery. At the last minute, the odds these men faced became even longer. The artillery that Lee expected to accompany the charge turned up missing, and no one told him. The charging Confederates also found that their two-hour barrage had fired too high, missing the front line of Union defenders. By contrast, the Confederate infantry presented a target so close that it could hardly be avoided by the Union guns. Pickett’s charge turned into a failure of historic proportions. Three thousand of his 4,500 men were killed, wounded, or captured. As the survivors staggered back to their own lines, Lee met them, outwardly composed but inwardly aghast. “It’s all my fault,” he told them. “It is I who have lost this fight, and you must help me out of it the best way you can.” The trouble was, there were a lot fewer of them to do that now. Twenty-eight thousand of them had been killed, wounded, or captured at Gettysburg, along with 23,000 Federals. * * * As Lee prepared his doomed attempt to sweep Meade from the field at Gettysburg on July 3, a ceasefire hushed the hills and chasms around Vicksburg a thousand miles to the southwest. There, from behind impregnable fortifications, Lt. Gen. John Pemberton’s 30,000 starving troops in the so-called Confederate Gibraltar faced 80,000 besiegers under Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant. Subsisting on mule and rat meat and despairing of rescue by another 30,000 Confederates lurking in the Mississippi interior under General Joseph E. Johnston, they now threatened mutiny. They were right about Johnston. He was a superb defensive general but close to zero as an offensive one, and he as much as told Richmond he had no intention of losing his small force trying to break Grant’s siege lines. So Pemberton sent Grant a note on July 3. In it, he proposed that the two of them name commissioners to draw up terms for a Confederate surrender. Grant’s reply outlined the same terms he had granted at Fort Donelson 16 months earlier: none. Unconditional capitulation only. Pemberton seems to have thought Grant’s reply was a negotiation ploy. When the two met face to face, Pemberton asked what terms Grant offered. The same as outlined in his note, Grant said. “The conference might as well end,” Pemberton said hotly, turning to leave. “Very well,” Grant said. They agreed, however, to continue to talk via couriers, and Pemberton issued a parting threat. With no surrender agreement, he said, Grant would “bury more of your men before you enter Vicksburg.” Grant replied with only a cold stare. It promised that his would not be the only gravediggers. Overnight, Union Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson, Grant’s favorite subordinate besides Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, made a shrewd suggestion. Grant could make surrender more attractive to Pemberton by offering to parole the Confederates then and there. That way, Union steamboats urgently needed elsewhere would not have to transport the captives north to Union prisons. And the captives, instead of going to Richmond for the formal paroling process, could just go home, spreading their message of defeat across the lower South. This would take advantage of the reported dissatisfaction of Vicksburg defenders hailing from Georgia and Tennessee, who were reported on the verge of revolt. Grant also cannily increased his leverage against Pemberton. He instructed his pickets to tell their Confederate counterparts of the contents of his offer before it was made. Having received that one concession, Pemberton gave up. It was July 4, the 87th anniversary of America’s initial Independence Day, and the significance of the date was not lost on either side. * * * But joy over the Gettysburg and Vicksburg trip-hammer blows to Confederate fortunes was not universal above the Ohio and Potomac rivers. To the contrary. On July 11, Irish and German immigrants rioted in New York against implementation of a new law conscripting every male between 20 and 45 who could not afford to hire a substitute. The result was the largest insurrection in American history. Union victors at Gettysburg had to rush to New York to help put it down. At least 105 people died, including police, soldiers, and sailors. But the most numerous victims were African Americans, presumably because the draft was seen as a vehicle to win a war fought for their benefit. A hurriedly evacuated building housing black orphans was burned to the ground, and several African Americans were hung from lampposts. The “diabolical…outrages,” said an account in the New York Times, included an assault by 400 men and boys on a black cart driver as he emerged from his stable after caring for his horses around 8 p.m. on the rioting’s first day. The mob, “beat him with clubs and paving-stones until he was lifeless, and then hung him to a tree opposite [a cemetery]…they set fire to his clothes and danced and yelled and swore their horrid oaths around his burning corpse. The charred body…was still hanging upon the tree at a late hour last evening.” The rioting went on for five days and was the largest of several such dramatic demonstrations of rage across the North in opposition to the draft law. The significance of the New York violence was huge. Perhaps most important, it offered an ominous sampling of the national grassroots appetite for extending constitutional–or any other kind of–equality to people who did not have white skin. {For more, see Battle Cry of Freedom by James M. McPherson, Oxford University Press 1988; The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001; The Civil War Almanac by John S. Bowman, ed., Bison Books 1982; Lee by Clifford Dowdey, Little-Brown 1956; The Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant by Ulysses S. Grant, Penguin one-volume reissue 1999; The New York Draft Riots by Iver Bernstein, Oxford University Press 1990; and The New York Times Complete Civil War by Harold Holzer and Craig L. Symonds, eds., Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers 2010.] |

1963 As the ripples of its Birmingham victory widened, the civil rights movement became an ever larger target of latter-day McCarthyism. The Kennedy Administration and racist Southern governors each tried to cripple it by innuendo. Manipulating both the Administration and the governors was the FBI’s paranoid director, J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover’s all-pervasive influence again intruded itself on July 2. When 15 African American leaders met at the Roosevelt Hotel in New York to decide whether to march on Washington, NAACP boss Roy Wilkins looked at the assembled group and, fearing Hoover-inspired charges of subversion, cut the total to six. It was a high-handed assertion of Wilkins’s power as head of the nation’s most historically dominant civil rights organization–and showed the extent of his fear of Hooverism. The nine men evicted from the gathering included ex-Communist Bayard Rustin and a New York labor leader who had provided office space to Rustin to promote the Washington march. The six men Wilkins allowed to remain in the meeting were Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, A. Philip Randolph of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality, John Lewis of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Whitney Young of the Urban League, and Wilkins himself. A Washington march had been proposed as early as 1941 by Randolph, and the head of the Sleeping Car Porters began the meeting by again espousing that massive project. He ran afoul of Wilkins, though, when he said he wanted the march led by Rustin. Rustin had worked against racial discrimination for the Young Communist League throughout the 1930s. But in 1941, when the Communist Party demanded that its operatives close ranks with other Americans against Hitlerism and stop activities that divided the U. S. homefront, Rustin quit the Party. Nevertheless, Wilkins now nixed Rustin. He said he would back a Washington march only if Randolph led it himself. Randolph consented on one condition: Rustin must be his deputy director. Wilkins, an initial opponent of the march, reluctantly agreed to support it on those terms–but declined to help “when the trouble starts” over the march’s “Communist” leadership. Wilkins’s refusal on this point, King thought, gave up the NAACP’s traditional dominance of the movement. * * * Wilkins’s decision to participate in planning the march at all was a bow to rising hope in black America. That hope, ever more obviously, was a product of the victorious Birmingham street campaigns of Wilkins’s longtime rival, King. In July, Wilkins swiftly saw with his own eyes that he had made the right call. He flew from the New York meeting to Chicago for the annual NAACP convention. There Mayor Richard Daley had just regaled opening ceremonies with a self-serving speech claiming Chicago had no ghettos. Outraged dissent swiftly materialized. When Daley led 10,000 NAACP members downtown in a Fourth of July Freedom March and then tried to make another speech to them, they booed him for 20 minutes. The uproar sent Daley fleeing to his limo. Then the Rev. J. H. Jackson, a black conservative and King opponent who had decried the Washington march as a dangerous overreaction, stepped to the microphone Daley had vacated–and was not just booed but also jostled and physically threatened by the angry crowd. Then James Meredith, hero of the 1962 desegregation of Ole Miss, rose to decry the march as an intrusion into politics by non-politicians. Boos rained on him, too. Publicly, the Wilkins-King antagonism dissipated. The NAACP chief appeared with King on television to promote the march, which was scheduled for Aug. 28. On-screen, Wilkins granted that King had “triggered” events that led President Kennedy to recently introduce a new civil rights bill. King in turn lauded Wilkins as the architect of civil rights legislation and strategy. But their old rancor was barely masked. In private, Wilkins chided King about the fact that it was NAACP legal action which reaped results from the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott that had brought King fame. King’s street marches, Wilkins added, had not integrated school classrooms in Birmingham or Albany, Ga.–or anywhere else. On one occasion, Wilkins tried to put down King by asking if his campaigns had ever “desegregated anything.” King one-upped him. About all he had desegregated, he replied, was “a few human hearts.” * * * But King, too, had to retreat in the face of Hoover’s inscrutable power. He reluctantly bowed to President Kennedy’s demand that he cut his ties with another man of past Communist associations, Jack O’Dell. O’Dell was manager of the direct mailings from the New York office of the SCLC and one of King’s most trusted advisers. Five years King’s senior, O’Dell had grown up Catholic in Detroit and had graduated from Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans. He had spent several years in the merchant marine during and just after World War II, and there, influenced by fellow black sailors, he studied the works of W.E.B. Dubois. Soon he began organizing for the National Maritime Union. King sent O’Dell, who had been a money-raising wizard for the SCLC, a heartfelt apology for parting ways with him. King praised O’Dell’s work “for your fellow man” and blamed the firing on the influence of McCarthyism. King sent the Justice Department a copy of his letter–to, doubtless, show the Department what it and the White House had done. But he flatly resisted in the case of Stanley Levison, his closest white friend, the volunteer adviser who oversaw the direct-mail operation O’Dell had been managing. Levison had worked with Communists during the 1950s against McCarthyism and in behalf of lifting racial oppression in the United States. But he had drifted away from the Communists years earlier, and King told the Administration that he had to have positive proof of Levison’s national treachery. There was a huge point here. If Levison was so dangerous, why had he not been tried, convicted, and imprisoned? King’s stiff resolve put the Kennedys in a ticklish spot. They had only Hoover’s word that Levison was dangerous. Hoover had declined to show even the President the proof, on grounds that it would compromise his sources and national security. So the Kennedys tried to bully King with what was meant to be the scariest innuendo yet. In response to his request to see the incriminating information, they sent Burke Marshall of the Justice Department to meet King’s representative, Andrew Young, in New Orleans at the Federal Courthouse. Rather than information, Marshall brought Young a chilling question: Did Young know who Rudolf Abel was? Abel, Marshall then informed Young, was the top Soviet agent ever convicted of spying. Levison, he went on to imply, occupied the same sort of position with the Soviets as Abel. Neither King nor Young bought it. Young later wrote that his own impression of Levison was of a “gentle, softspoken man whom I considered conservative” because he always advised King to look long at any course before deciding to follow it. After asking Marshall to produce documents backing the Administration’s claim and being told no, Young asked Marshall if he himself had ever seen such documents. Marshall had to say no. On July 16, King sent a representative, Clarence Jones, to tell the Administration what he planned to do about Levison. Assuming the problem had to do with politics rather than spying, King said he would lessen the Administration’s openness to segregationist attacks by no longer communicating directly with Levison. He added, however, that he had received no evidential reason to stop conferring with Levison indirectly. Just three weeks previous, in their private walk in the Rose Garden, the President had told King that FBI-bugged telephone conversations between King and Levison were prompting the charges that the civil rights movement was Red-infiltrated. King’s solution, King said, would leave nothing for the bugging to pick up and thus would cut off the ongoing basis for the allegations. Andrew Young later noted that Hoover lied to the White House by attributing his information not to his bugging of King-Levison telephone calls but, rather, to “a reliable informant,” implying that his “information” originated inside the Communist Party. This made it look as if King were, intentionally or otherwise, aiding in the work of the Party. Young added that documents which eventually became public under the Freedom of Information Act “and everything else we’ve learned” had not changed his mind. They never provided an indication that, during his friendship with King, Stan Levison was in contact with the Communist Party. “I can only conclude,” Young added, “…[that] there wasn’t any.” The bugs, Young wrote, were not an attempt to foil an impending plot to overthrow America nearly so much as they were meant to give the FBI and its white supremacist director “a listening post to learn about Martin’s plans and strategies.” But, thanks again to the Kennedy Administration, the wiretap problem got worse. Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy– surely fearing that somebody close to King might mention on a wiretapped conversation the President’s warning to King that he was being bugged and that Hoover might then leak that information to Kennedy’s segregationist enemies–requested that the FBI ask him for a more extensive FBI wiretap of King. It would cover wherever he went. Kennedy asked for one also on King operative Clarence Jones. But once the attorney general received Hoover’s request for the wiretaps he himself had requested, he rethought. As much as he needed to keep Hoover halfway happy, he also needed not to alienate African Americans, who had done much to put his brother in office. On July 25 Robert Kennedy exonerated the civil rights movement’s leadership, including King, on the charge of being controlled by the Communist Party. That day he signed Hoover’s request for a wiretap of Jones–but changed his mind on King. He sent back unsigned Hoover’s request for the sweeping new taps affecting King. [For more, see Parting The Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1988; An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America by Andrew Young, Harper Collins 1996; and Racial Matters: The FBI’s Secret File on Black America 1960-72 by Kenneth O’Reilly, the Free Press 1989.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta