|

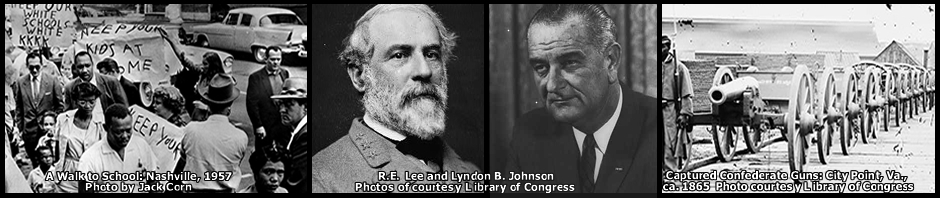

1863 The Union’s Vicksburg campaign had stalled for months, but not for lack of effort. To assault the 16 miles of cannon-bristling bluffs facing the Mississippi River situated from north to south of the town would be suicide. So for months Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had had his men try to get boats and troops to the town’s vulnerable landward side by digging canals, blasting levees, deepening shallow river channels, and chopping through tree-choked bayous. In vain, he and they had exhausted every water route available. Except one. That was the mighty Mississippi itself, the risks of which were daunting. The Father of Waters represented a last, desperate, daring alternative on which Grant had gone to work as grimly as he had all the others, if not more so. During late March he had closeted himself with just his maps and dozens of cigars and come up with a plan that flouted the most elemental military strategy. The plan called for marching most of his army down the Louisiana bank of the Mississippi to Hard Times Landing, well south of Vicksburg. In the meantime he would also send Federal gunboats and transport vessels under cover of darkness downriver past the Vicksburg guns. It was an all-or-nothing gamble. Because of their low power, these boats would be unable to come back upstream, and he had no others. Thus did Grant irrevocably commit himself to a very long shot which would get even longer if and when he could reunite his army and boats below Vicksburg. There he proposed to use the boats to accomplish the crossing of the widest body of water by the largest number of troops yet achieved in history. Then he would cut all but the most tenuous ties to his supply base and plunge into the Mississippi interior to try to surround the bluff fortress. Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, his subordinate and close friend, was horrified. He attributed the desperation of Grant’s move to fear of losing his job. “Grant trembles at the approaching thunders of popular criticism,” Sherman wrote his wife, Ellen. It was true that Grant had become all too acquainted with criticism. There had been storms of it after Shiloh, and now his men’s prodigious labors through the swamps and bayous had got them nowhere. A reporter for the Cincinnati Gazette had described them as “thoroughly disgusted, disheartened, demoralized” because they were commanded by “such men as Grant and Sherman.” The Gazette’s editor wrote federal Treasury secretary Salmon P. Chase that Grant was “foolish, drunken, stupid” and an “ass.” Another prominent Cincinnati journalist told Chase that Grant was an utter “jackass.” But Sherman’s proposed alternative to Grant’s unthinkable gamble was worse. Sherman begged Grant to take his troops back to Memphis and return to their initial route southward through central Mississippi–the one Grant had abandoned after December raids by Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest in West Tennessee and Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn in northern Mississippi had slashed his rail supply line to pieces. Grant believed that the North’s war-weary populace would not tolerate another attempt to start over. On April 1, Grant took a last look at a prospective attack site north of Vicksburg and found it wanting. The cliffs there overlooked too small a shelf for troops to land and form for an attack. He turned his attention southward. * * * Meanwhile, the fortunes of the governments north and south continued to spiral into new depths of angst and want. On April 2, Richmond saw a bread riot which brought Confederate President Jefferson Davis into the streets to warn that people would be shot by nearby militiamen if they did not disperse within five minutes. “We do not desire to injure anyone, but this lawlessness must stop,” Davis said. The mob dispersed after several arrests and no injuries, but the import was stark: Hunger was spreading in Dixie. Eight days later, Davis urged Southern farmers to forget money crops like cotton and tobacco and plant their fields with food. On April 24, the Confederate Congress approved a harsh taxation measure: 8 percent on all agricultural products; 10 percent on profits from selling food, clothes, and iron; and a graduated income tax. Common citizens regarded the tax on farm products as particularly harsh. In a further indication of the shrinking of Confederate resources, even human ones, Jefferson Davis on April 16 signed into law an act providing that soldiers under age 21 could be commissioned as officers. Confederate hopes abroad continued to dim. On April 5, Britain finally moved to seize and impound several Confederate ships being built there. Some of these would eventually be released, but the cooling of the English government’s attitude toward Southern independence, and a warming of feelings for the North, were obvious. The North’s problems loomed large, too. On April 7, the Federal navy sent nine ironclad gunboats against the port of Charleston, S.C. The harbor forts Sumter and Moultrie responded with a devastating barrage that badly damaged several of the boats, including one that sank the next day. Admiral Samuel DuPont decided Charleston harbor was too strong to conquer by a naval operation alone. On April 13, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, now commanding the Department of the Ohio after his disastrous turn leading the Army of the Potomac, proclaimed that sympathizers with the Confederacy were to be deported southward–and persons convicted of actively helping the Southern cause would be executed. In mid-April, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, Burnside’s replacement as commander of the Army of the Potomac, said that his total troop strength was around 130,000. He was opposed by some 60,000 men under Confederate General Robert E. Lee. On April 17, a Federal raid aimed at Confederate munitions-making facilities in eastern Georgia departed Tuscumbia, Ala. Two days later, the Union force defeated pursuing Confederates at Sand Mountain, but the Federal commander learned disturbing news: the Confederate pursuit had not been stopped, and it was led by none other than the intrepid Confederate “devil,” Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest. In late April, Hooker with 70,000 men crossed the Rappahannock River heading for Chancellorsville, Va. With typical bluster, he reported that his “operations of the last three days have determined that our enemy must ingloriously fly, or come out from behind their (sic) defenses.” Any Eastern Federal commander should have known by then that he could be guaranteed one thing: Robert E. Lee would not ingloriously fly. * * * Down on the Mississippi, Grant set his daring plan in motion. He sent 20,000 of his troops, 6 million pounds of small arms ammunition, and 10 six-gun artillery batteries with 300 rounds per gun on a 37-mile trek southward from Milliken’s Bend, La. Subordinate Maj. Gen. John McClernand, commanding this move, estimated that it would take his 150 available wagons three trips and 13 days to transfer these men and materiel to New Carthage, La., where they were to meet the gunboats and transport vessels Grant planned to dispatch downriver past the Vicksburg cannons–provided that those vessels survived the certain Confederate barrage. Grant’s assignment of the troublesome McClernand to command this important mission seems to have been partly attributable to prudence and to the situation on the ground. McClernand’s troops were camped near the downriver route to be taken, and Grant likely did not wish to create an unnecessary problem with McClernand’s powerful friend, President Lincoln, until circumstances became more favorable. On April 16 Grant sent the boats. It was a dark night, and Confederate officers at Vicksburg were holding a ball in celebration. They thought Grant had given up his Vicksburg ambitions and was sending the boats downriver to aid in operations in the area above New Orleans. He wasn’t. To the dark and the river, he consigned seven gunboats, three transports, and a dozen barges. As he and his family watched from his headquarters boat, the vessels made it partway down before the Confederates discovered the ploy. Then they lighted huge fires on both banks for visibility, torching even entire houses, and they proceeded to fire 525 cannon shots at the passing collection of Union craft. But all except two of the boats made it downriver. When April ended, Grant himself was some 40 miles south of Vicksburg, finally on the threshold of the object he had lusted after for months: a chance to fight Vicksburg’s Confederate defenders at better than impossible odds. [For more information see The Papers of U. S. Grant, vol. 7 by John Y. Simon, ed., Southern Illinois Press 1979; War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, vol. 24, part 3, U. S. Government Printing Office 1880-1902; The Vicksburg Campaign, vol. 2 by Edwin C. Bearss, Morningside Press 1986; and The Civil War Almanac by John S. Boatner, Bison Books 1982.] |

1963 The Birmingham campaign, the battle for the very life of the civil rights movement, now finally got going. It opened modestly on April 3. That was the day after the city election in which comparatively moderate mayoral candidate Albert Boutwell defeated virulently racist police commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor. Local leaders hailed Connor’s defeat as a move toward long-needed improvement in the city’s image of brutal racial oppression. The Birmingham News ran a statement from the new mayor on the front page topped with a representation of a rising sun. On that same day, a couple of dozen college students and ministers materialized in front of four local eateries–a cafeteria, a drugstore, and two department-store lunch counters. When they sat down in seats traditionally reserved for Caucasians, the proprietors reacted, informing white patrons that they were closing for the day. Everybody, white and black, had to leave. The fight was on. The question, though, was whether anybody would notice. The leader of the incipient campaign, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was perceived as passé. He had not occupied national headlines in eight months, since an extended attempt to desegregate the much smaller town of Albany, Ga., became moribund the previous autumn. Slippage of King’s image was not the only problem. Such attention as the national press cared to give the Southern civil rights movement was now focused on Mississippi and Georgia. * * * Bob Moses and other stalwarts of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee such as Diane Nash had been putting their lives on the line for months to try to register black voters in Mississippi. Their success had been scant, opposed at every turn by the continual tactics of beatings and assassination with which the South had metthe threat of racial confrontation for centuries. Desperation drove the reformers to desperate measures. On Jan. 1, Moses filed a lawsuit against Attorney General Robert Kennedy and FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, seeking to require them to enforce portions of U.S. law making intimidation of prospective voters a crime. The FBI was included in the suit because its agents were making no attempt to enforce voting laws in Mississippi; they just watched and gathered information. But the Justice Department blocked Moses’s measure. The foot soldiers for civil rights wouldn’t quit, though, and Mississippi news grew more plentiful as the winter wore on. State officials quit distributing federal food surpluses to two central Mississippi counties where SNCC and the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) concentrated their voter registration efforts. These were Sunflower, home of U.S. Sen. James O. Eastland, and LeFlore, headquarters of the White Citizens Councils of Mississippi and home to 22,000 poor and mostly-black people who had their food relief cut off. The yearly income of a good third did not reach $500. Outsiders began to notice. On Feb. 1, Harry Belafonte and the Albany Freedom Singers headlined a benefit concert at Carnegie Hall in New York. In Chicago, comedian Dick Gregory announced that he had chartered a plane to carry seven tons of food to the affected area. Many more tons of food arrived, and the pressure had built during February. Greenwood received attention in the New York Times. Bob Dylan, a rising folk star, arrived to sing his pointed hit “Blowin’ In The Wind” to a small African American crowd. Mysterious fires erupted around SNCC’s Greenwood headquarters, and a SNCC volunteer was shot in the shoulder and neck as he drove on a nearby highway. When another car carrying civil rights workers was fired into on the night of Mar. 6, Greenwood’s mayor publicly hazarded the guess that SNCC had staged the shooting for publicity purposes. In late March, SNCC’s Greenwood office finally went up in an arsonist’s flames, and nighttime assailants fired a shotgun at a local black activist. The mass meetings held in response to the violence finally produced a crowd of 150 who marched to the registrar’s office. To disrupt and disband this demonstration, police loosed a vicious dog that tore Bob Moses’s pant leg and bit another marcher so seriously he was hospitalized. As April opened, civil rights leaders began pouring into Greenwood. They included the NAACP’s Medgar Evers, the Congress of Racial Equality’s James Farmer and David Dennis, and Charles McDew of SNCC. Dick Gregory arrived to lead three marches to the courthouse, only to be turned away each time. He then interrupted Greenwood’s Mayor, Charles Sampson, as Sampson was solemnly listing character flaws that he said disqualified blacks from voting. “Well, now, Mr. Mayor,” Gregory said with a wide grin, “you really took your nigger pills last night, didn’t you?” Justice Department officials arrived on Apr. 3, and in negotiations that day, the Greenwood city fathers backed down. They suspended the sentences of eight SNCC workers and freed them. * * * Meanwhile, more focused outrage occurred in Columbus, Georgia. There in early April a jury took less than half an hour to acquit a county sheriff who had shot an Albany African American civil rights sympathizer three times in 1961 while the man sat handcuffed in the sheriff’s squad car in “Bad Baker” County. In response, local African Americans began to picketing a black-patronized grocery store owned by one of the white jurors. Several demonstrators were arrested, and a lawyer for the grocer filed a civil lawsuit against the Albany Movement for staging an illegal boycott. The same attorney contacted the local bar association as well as the Justice Department in Washington and charged that the blacks had obstructed justice by launching their action against the grocer because of his work on the jury. In nearly as much of a travesty of justice as the trial, the Kennedy Administration sent 30-some FBI agents to Albany to question a horde of local African Americans. * * * Compared to the events in Georgia and Mississippi, an incipient campaign by Martin Luther King targeting Birmingham seemed distracting or worse. This was especially true for most Birmingham blacks on whom he was counting for its support. The number of marchers willing to go to jail in the days approaching Easter was minuscule. Fellow ministers, even in King’s innermost circle, resisted. No less than the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, King’s virtual co-leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was determined to go home to preach in his Atlanta church on this biggest of dates on the Christian religious calendar. And there was ample reason not to march. Blacks whom King branded “traitors to the Negro race” had begun breaking the intended boycott of downtown businesses and buying Easter clothes. Money to bail the marchers out of jail was already low, and Alabama Gov. George Wallace had come up with a new law raising the bail demanded for misdemeanors—in Birmingham only—from $300 to $2,500. And Birmingham authorities prepared an injunction against demonstrating by African Americans. In eight days of demonstrating, King’s campaign had put a mere 150 persons in jail, nowhere near enough to cause the city any economic or crowding problems. With Wallace’s new bail law, the poorest of the prisoners might have to stay six months. So King had to ponder whether to renege on his pledge to go with them and instead go back north to raise bail money, meanwhile risking finding no Birmingham movement left when he returned. After the latest of several contentious meetings with his advisers on Good Friday, April 12, King withdrew to the bedroom of his suite at the Gaston Motel. A few moments later he emerged startlingly transformed. Instead of his characteristic suit and tie, he was dressed in a work shirt, jeans, and farm-style brogan boots. “If we obey this injunction, we’re out of business,” he explained to his thunderstruck advisers, who knew that only 50 people had volunteered to accompany him on the Good Friday march. “I am going to march, if I have to march by myself.” He didn’t have to, as it turned out. In addition to the 50 volunteers, Abernathy decided at the last minute to go, too. An estimated thousand blacks gathered to watch, and they cheered the two ministers and their little band as police roughly grabbed them and shoved them into paddy wagons. The officers then made a mistake. They did not put King into a cell with other prisoners. Rather, they placed him in solitary confinement—“the hole,” as they called it. Utterly unintentionally, they had done him a favor. Suddenly, he was forcibly relieved of the myriad responsibilities of leading his movement and flying back and forth across the country to gather the money to fund it. With the company of only a couple of books and some newspapers brought to the jail by followers, he was free to think. And write. In the margins of a newspaper, with a maze of arrows indicating which paragraphs followed which, he began writing a long letter to the world. [For more information, see The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation by Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, Alfred A. Knopf 2006; Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1988; and In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s by Clayborne Carson, Harvard University Press1981.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta