|

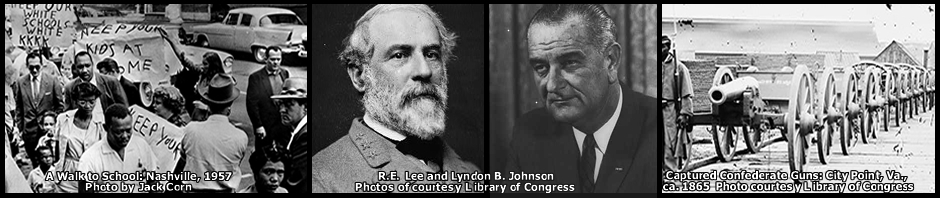

1863 Abraham Lincoln had shaken too many hands. For more than two hours, New Year’s Day guests pumped his arm at a public White House reception. But the President did not look joyous. A British volunteer surgeon for a Washington hospital attended the function and wrote that the Chief Executive appeared “miserable.” A journalist more familiar with him said Lincoln’s walk that day appeared “more stooping,” his face “sallow,” and that his “large, cavernous eyes” projected a “sunken, deathly look.” It was no happy new year. Rather, it opened full of cares, especially for the man most responsible for holding together the broken, bleeding Union. Down at Murfreesboro, Tenn., a great multi-day battle was not going well. On Dec. 31, Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans had planned a dawn attack on General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee aound Stones River, but Bragg had beaten him to the punch. The Confederates mauled him badly enough that Rosecrans and his generals considered retreating overnight. They hadn’t done it, though, and today, with maneuver and skirmish, they prepared to resume bloody all-out fighting. Also on this first day of 1863, Confederate troops and cotton-buffered gunboats attacked and dispersed a Federal garrison at Galveston, Tex., repossessing the island city for Jefferson’s Davis’s government in Richmond, Va. Back in Washington, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside came by to resign. Two weeks earlier the general had ordered his 120,000-man Army of the Potomac forward into senseless slaughter at Fredericksburg, Va. More than a tenth of Burnside’s total force had become casualties. But, for the moment, Lincoln turned down Burnside’s offer to quit. He had no immediate replacement. Even the day’s most positive act was fraught with worry. After the prolonged handshaking at the reception, Lincoln worried that when he signed the Emancipation Act into law, he would not be able to hold his hand steady, and history would conclude from his shaky signature that he had had reservations. He said he did not. “I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right than I do in signing this paper,” he said. Little wonder, though, if it gave him pause. The act was no less than an attempt to begin finally trying to deliver on the grandiose promise the United States had made to its people and the world in the Declaration of Independence 87 years before. “All persons held as slaves within the said designated States,” this new law said, “are, and henceforward shall be, free.” The “said designated States” was a major caveat. No slaves within states that had remained in the Union–nor even ones belonging to owners in Tennessee or parts of other states that had come under federal control–were yet freed. So skeptics scoffed. Then and later, down to now, some have condemned it as an empty fraud that liberated no one, just a desperate gamble to gain leverage in a war that looked increasingly unending. It was most definitely the latter, but the former could hardly have been less correct. Even if at that moment it freed no one, there was nothing empty about it. Lincoln himself had hesitated to do it because of its enormity. Once declared, it could not be taken back, and it struck at the Confederacy’s essence. Slaves comprehending freedom, even in prospect, would never again have the same relationship with their masters. And the masters knew it. There was an even farther-reaching aspect to the new law, too. It permitted freed slaves to join the Union Army and oppose their erstwhile masters with bullets. * * * After the interim day of maneuver and skirmish, the battle of Stones River resumed in bitter cold on January 2. Bragg sent Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge forward on the Confederate right before dawn. Breckinridge, protesting that it was suicide, nonetheless complied, and his men surprised the Federals. But crowds of Union guns on the opposite side of Stones River stopped Breckinridge, threw him back, killed two of his generals, and drastically winnowed his ranks. Then Federal infantry crossed the river to recover the lost ground and exploit the artillery’s work. After waiting through the daylight hours of Jan. 3 to see if Rosecrans would retreat, Bragg himself did so after nightfall. This decision helped prompt his generals to question his competence as a commander. Both sides had lost heavily–13,000 of 41,000 Union troops, nearly 12,000 of 35,000 Confederates. Down on the Mississippi River, an eventuality Union Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant had sought to avoid finally happened. Political general John McClernand, who had wheedled an independent command out of his longtime acquaintance Lincoln, arrived near Vicksburg and took command in the wake of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s bloody late-December repulse there. McClernand had known and sometimes partnered with Lincoln in law cases back in antebellum Illinois, and he wielded this cachet like a club. He had resigned a seat in Congress to become an Army officer, and early in the war he had become a principal thorn in the side of Grant, his immediate superior. McClernand or his staff likely provided the source for scandalous charges of chronic alcoholism that were filed against Grant in the Union chain of command before Grant left Cairo, Ill., on the Fort Henry-Fort Donelson campaign. Even before that, following Grant’s nearly disastrous raid in November 1861 on Belmont, Mo., Grant aide and confidant John Rawlins complained loudly to other Grant staffers that McClernand was a “damned slinking Judas bastard.” On Jan. 11, borrowing a Sherman idea, McClernand attacked Fort Hindman in Arkansas. Better known as Arkansas Post, the fort had provided a base for Confederates who attacked Union shipping on the Mississippi. Grant first decried the attack as a “wild goose chase,” then changed his mind when he learned that his friend Sherman had proposed it. The attack succeeded. It cost McClernand’s 40,000-man force 1,000 casualties, but that was a fair swap for capturing the fort and nearly 5,000 prisoners. * * * The tiny Confederate navy by now had begun making itself a fearsome reputation. The Alabama and the Florida, in particular, focused on disrupting U.S. merchant shipping. The Alabama, built in England and captained by Maryland-born attorney and Mexican War veteran Raphael Semmes, had already sunk 10 merchant ships when it approached Galveston, Tex., on Jan. 11. There Semmes found five U.S. Navy warships blockading the port city. He thereupon lured one of them, the Hatteras, 20 miles away from the others and sank it in a short but lethal battle. On Jan. 17 the Florida, another British-made Confederate vessel, set out to emulate Semmes’s exploits. It made a successful midnight run past the Federal blockade of Mobile Bay in Alabama and headed for open sea. * * * Back in Virginia, his resignation unaccepted, hapless General Burnside tried once more to go into action to again surprise Robert E. Lee at Fredericksburg. It was not to be. The heavens opened with two days of cold rain, rendering roads bottomless. The Mud March, as Burnside’s movement became known, stymied him and, after two numbing days, sent him slogging back where he had started from. Lincoln then gave up on him. On Jan. 22, the President replaced him with “Fighting Joe” Hooker, a hard-drinking bon vivant and inveterate schemer against superiors. Hooker was more aggressive than some other Union officers but not quite as combative as his nickname proclaimed. The sobriquet itself was fraudulent, product of a newspaper headline intended to give a situation report from the front. It meant to say, “Fighting–Joe Hooker,” but a typographical error removed the dash. The day before appointing Hooker, Lincoln revoked a highly ill-advised order from his best western commander. U. S. Grant’s infamous General Orders No. 11 had expelled all Jews from his department because of widespread and successful efforts of merchants–of varied ethnic backgrounds, not just Jewish–to obtain captured Southern cotton through bribery and other corruption. The order had already unjustly evicted and expelled several Semitic families with only what they could carry, and Lincoln stopped it. He sent word to Grant that no such action could be taken against an ethnic group that included some of Grant’s own soldiers. But six days later, on Jan. 27, the President himself committed an act of a type for which his administration, albeit a wartime one, would remain controversial for 150 years. He ordered the arrest of A. D. Boileau, publisher of the Philadelphia Journal, for publishing materials in opposition to the Lincoln government. Lincoln’s philosophy held that, in a crisis, violating one rule of the Constitution to safeguard all the others was justified. That such things should even be considered, though, was a sign of the times. By the beginning of 1863, with this steadily-bloodier war approaching the onset of its third full year of fighting, unattractive choices were the norm. [For further information see Lincoln by David Herbert Donald, Simon & Schuster 1995; The Civil War Almanac by John S. Boatner, Bison Books 1982; A World On Fire by Amanda Foreman, Random House 2010; and The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001.] |

1963 By now a bloody truth had become more than obvious to civil rights leaders. The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution with its Reconstruction amendments, and even the Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling that school segregation was unconstitutional were not enough to get African Americans their rights. “We needed a national law that created an affirmative obligation not to discriminate and established penalties for disobedience,” later remembered Andrew Young, then director of voter registration training for the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference. It was also distressingly apparent that the amount of pressure needed to get such a law written and introduced was going to require more than just the lukewarm Democrats led by President John F. Kennedy or the progressive Republican followers of New York Gov. Nelson Rockefeller. Civil rights leaders needed a civil rights bill, Young said. And to show their need for it they had decided to take on Dixie’s most proudly racist city. Birmingham, Alabama. * * * Challenging Birmingham was a lofty aspiration for a movement that had failed miserably a few months earlier in much smaller Albany, Ga. But there was a promising difference in the two campaigns. The one in Birmingham would not be a conglomeration of efforts by such other organizations as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, the NAACP, and King’s late-coming SCLC. Unlike Albany, the Birmingham campaign would be launched and directed solely by the King organization. In early January, King gathered 10 aides for a secret strategy meeting in Dorchester, Ga. Those invited were Alabama specialists or indispensable in other ways. They included two prominent Alabama-rooted ministers, Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham and Joseph Lowery of Mobile; well-traveled civil disobedience coach James Lawson; four top leaders from the SCLC’s Atlanta office–Wyatt Walker, Ralph Abernathy, Dorothy Cotton, and Andrew Young; and three money men: Hollywood entertainment lawyer Clarence Jones, wealthy New York car dealership mogul and SCLC financial director Stanley Levison, and Jack O’Dell, onetime Birmingham insurance salesman now handling Levison’s direct-mail solicitations for King’s organization. Dorchester, Ga., was the site of the SCLC’s so-called Citizenship School Program for training prospective voter registrants across the South. Its director, Young, had been little more than an observer in the Albany campaign, despite having previously served a stint as pastor of a church in nearby Thomasville, Ga. His inclusion in the secret meeting at Dorchester signaled that his role would be much expanded in Birmingham. King could hardly have picked a better major subordinate face of the new campaign. A native of New Orleans, Young had moved from the Thomasville pastorate to work in New York for the National Council of Churches with mostly white colleagues. Now Young was to have charge of recruiting, organizing, and training opponents of Birmingham’s entrenched racial injustice. He would be assisted by three of the earliest, toughest, and most innovative front-line fighters for civil rights in the entire movement: philosophical guru James Lawson along with fiery and eccentric young preacher Jim Bevel and his wife, the equally brilliant and far more level-headed Diane Nash. Nash was the unquestioned queen of the Nashville sit-in movement and the indomitable brains behind crucial Nashville reinforcement of the first, faltering Freedom Rides. In Birmingham, there was to be no willy-nilly approach, no off-the-wall confrontations by a variety of well-meaning civil rights groups. SNCC, which Nash and Bevel had exited to join the SCLC the previous fall, was not working in Birmingham and had no plans to. And the NAACP had long since been outlawed in Alabama. At the Dorchester school, Young and other members of the staff had taught a systematic four-step method developed by Mahatma Gandhi, the Indian pioneer of nonviolent demonstrations. The steps were (1) investigation of the target area; (2) communication and negotiation with the target; (3) confrontation with the target; and (4) reconciliation with the target. Wyatt Walker, charged by King with outlining a skeleton campaign plan, had come up with one that dovetailed with the Gandhian approach. Walker’s scenario called first for small demonstrations to garner initial attention; then a boycott of businesses in downtown Birmingham in tandem with growing demonstrations; then even larger demonstrations to put teeth in the boycott; and finally, if need be, appeal to Northern supporters to flood into Birmingham to help. While Walker handled the media and kept track of the campaign’s financial resources, Young’s job would be to meet and get to know members of the Birmingham black community and begin training them in Dorchester-like workshops. But Young also got the group’s approval to contact the white establishment before the demonstrations began. He felt “we needed to begin talking early, before the polarization started, and to keep talking to speed up the process of reconciliation.” He had learned as far back as his early days of trying to foster racial progress in Thomasville that the financial vulnerability of merchants could make the business community an ally. They “would feel the pinch of an effective boycott and in turn would persuade political leaders to act,” Young later wrote. “We (at the Dorchester meeting) all agreed that the city’s pocket(book) was the best place to start applying the pressure.” This tactic would also take advantage of another potential underlying weakness of Birmingham’s racism. The city’s financial backbone was the steel industry, whose home offices were in the North. Their more moderate sensibilities could provide leverage for an attack on the city’s overt discrimination. Another help would be Fred Shuttlesworth’s lengthy leadership of a group called the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, which had been holding weekly mass meetings for seven years. A likely downside, though, was the conservatism of the city’s Negro Ministerial Association, which might well oppose the SCLC campaign. As the clandestine 11 hammered out details of their Birmingham plan over three days, they took time-outs in the afternoons. To clear their heads, they played softball and basketball, then went back to work in evening sessions. The final plan was to mobilize their boycott for March. That would put it in full swing by Easter, the occasion around which many black families bought most of their clothes for each year. Unlike in Albany, the Birmingham campaign would forge extensive ties within the black community from the beginning and discourage members of that community from making separate, individual arrangements with the white establishment. Finally, for the campaign they would move much of their Dorchester training machinery to Birmingham to develop their demonstrators and tactics on the spot. * * * The Dorchester conclave was secret, but not completely. J. Edgar Hoover’s Federal Bureau of Investigation knew it was happening. An FBI wiretap had picked up a call from Clarence Jones to Stanley Levison about the fact that the exclusive gathering was to occur. But King had kept its purpose so quiet that no FBI informant inside the Movement had any idea what the meeting was about. As it turned out, King might have been better off sending Hoover a daily memo of the proceedings. The paranoid FBI director thought King was holding what amounted to a cell meeting of the foremost object of Hoover’s obsessive fear, the Communist Party. Hoover went to great lengths to have FBI agents surreptitiously film the arrival of the 11 at the Savannah airport. That Levison and O’Dell were included in the group made it look all the more menacing to Hoover. He had long known and exaggerated the socialist/Communist leanings of the two men, and in November King had responded to a New Orleans newspaper article about O’Dell by falsely claiming O’Dell’s participation in the SCLC had been minimal and that he had resigned from the organization. King already had satisfied himself about O’Dell’s national loyalty. He knew that O’Dell had been ejected from the National Maritime Union and that the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1958 had branded him a suspected Communist. In the wake of the New Orleans magazine article, King questioned him, and O’Dell contradicted the newspaper’s assertion that he was a member of the American Communist Party’s central committee. O’Dell told King he was not a member of the central committee or even the party, but that he had attended some party meetings and had written a piece on the Louisiana political scene for a Communist periodical. Hoover memoed Atty. Gen. Robert Kennedy about the Dorchester meeting. It was part of an ongoing Hoover effort to engender fear in the Attorney General, who saw American Communists as minimally dangerous. Hoover’s tactic appeared to have at least some effect. “Burke–this is not getting any better,” Kennedy wrote a staffer on one of the Hoover notes. Assistant FBI director Cartha “Deke” DeLoach, in a memo of his own, cast King as a “vicious liar,” and, partly as a result of the secret Dorchester meeting, the Bureau came to regard King as a national peril to the safety of the United States. The Bureau routinely warned potential victims when its intelligence learned that they were targets of murder threats. From now on, though, it would accord King no such help. [For further information, see Parting The Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1988; and An Easy Burden: The Civil Rights Movement and the Transformation of America by Andrew Young, HarperCollins 1996.] |

-

Archives

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

-

Meta