1861

Major General John C. Fremont’s August 30 proclamation of martial law and emancipation of rebel-owned slaves in Missouri caused a September sensation. Well, several sensations.

The New York Times of Sept. 2 hailed Fremont’s emancipation edict as “by far the most important event of the war.” The newspaper pointed out that Fremont had not declared wholesale emancipation in the Show-Me State; his proclamation applied only to slaves serving Confederate sympathizers. As such, it was simply and solely a military and thus fully constitutional measure designed to weaken the South.

Without it, the New York paper noted, Southerners could truly affirm what they had already boasted: that all their white men could go to battle without hampering the Confederacy’s internal production of supplies of war. The North, by contrast, would have to sap its own industrial and agricultural strength to put armies in the field.

But the Times noted a downside, too. The South would wrongly see Fremont’s as a long step toward the freeing of every slave, the specter that had prompted secession. The Times did not note that radical abolitionists saw it the same way, reacting with as much joy as Southerners did with horror.

President Lincoln was suspended between these two extremes. He still had restless Maryland and neutral Kentucky to worry about. A friendly political observer in Kentucky wrote Lincoln that if he did not soften Fremont’s declaration, the Bluegrass State was “gone over the mill-dam.” Even in Missouri, Frmont’s declaration seemed likelier in the short run to foment, rather than reduce, resistance to Federal authority. He had issued it from a position of weakness, just after the important Confederate victory at Wilson’s Creek.

Lincoln sent a restrained letter to Fremont on Sept. 2. Stressing that he wrote in a “spirit of caution and not of censure,” he said Fremont’s measure would undermine Southern unionism. He asked that it be modified to conform to the recent congressional act confiscating only slaves actively working for the Dixie military. Meanwhile, he sent Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, brother of Missouri congressman Frank Blair Jr., to St. Louis to assess and ease the situation.

Fremont balked. His wife, Jessie, daughter of the late and longtime Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, rushed to Washington to upbraid the President. Implying that her husband–the Republican Party’s presidential nominee in 1856–was more intelligent than Lincoln, she said the proclamation would aid the North in staving off European recognition of the Confederacy.

Lincoln, of course, had to worry about losing the war before news of Fremont’s act could even reach Europe. He certainly did not need Jessie Fremont handing him a letter from her husband refusing to change a word of the proclamation without being publicly made to by the President. Lincoln had one of the most controlled tempers of anybody on either side of this war, but he lost it with Mrs. Fremont. He told her that the conflict was over “a great national idea”–preservation of the Union–and that her husband never should have “dragged the negro into it.” Her behavior from start to finish of their interview was so presumptuous that he did not invite her to sit down.

He soon withdrew Fremont’s sweeping proclamation. Unionists in the border areas hailed his action as again saving their states for the Union. Abolitionists howled. Typical was Senator Ben Wade of Ohio, who cited Lincoln’s commoner background and said his views were characteristic “of one born of poor white trash and educated in a slave state.”

Fremont’s Missouri pursuits yielded mostly disappointment. He arrested Frank Blair Jr., whose family had pushed Fremont’s appointment to run the department. Until too late, he also refused to go to the aid of a force of 2,800 Federals bottled up in Lexington, Mo., by 7,000 state militiamen under Sterling Price. Besieged on Sept. 13, the troops held out until Sept. 20. Then, nearly out of ammunition and water, they surrendered themselves and seven cannon, 3,000 rifles, and 750 horses.

Left with little choice, Lincoln began casting about for a Fremont replacement. By then, though, the disappointing general had made his greatest contriibution to the war. He had given the Union a game-changing gift that it might never have gotten otherwise. In August, choosing the hands-on commander of the campaign down the Mississippi River, he had ignored a fellow egotist in General John Pope, in-law of Mary Todd Lincoln. Instead, he had conferred that honor on an obscure brigadier general of no pedigree, of alcoholic reputation, and a name ringing with incongruously high-flown overtones: U. S. Grant.

Fremont would later say he gave Grant the job because Grant was quick about following orders and had a will of iron. More likely, Fremont assumed the lowly Grant, unlike the self-important Pope, was less apt to become a Fremont rival.

For whatever reason it was made, the choice was immediately productive. Grant had not yet reached his new base at Cairo, Ill., when Confederates waiting just south of the Kentucky-Tennessee state line violated Kentucky’s tenuous neutrality. On September 3, they grabbed the commanding bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River at Columbus.

Both sides had coveted this spot. From it, cannon fire could rake and block southward navigation of America’s primary river. When Grant saw that the Confederates had taken it, he responded virtually overnight. Requesting Fremont’s permission but not waiting to receive it, he snatched two even more strategic Kentucky points, the towns of Paducah and Smithland at the mouths of the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers. These two great tributaries of the Ohio invited conquest. They outflanked Columbus and plunged into the Confederacy’s very heart.

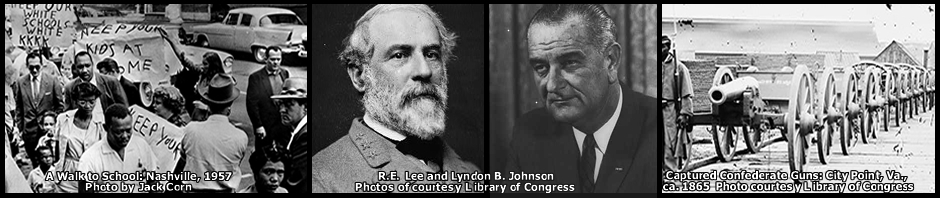

In western Virginia, another general of whom much more would eventually be heard was struggling. General Robert E. Lee’s only Confederate service so far had been as the taken-for-granted military adviser to President Jefferson Davis. Then he had been sent west to rectify a sorry command situation involving four brigadier generals–former Virginia Gov. Henry Wise, former U.S. Secretary of War John B. Floyd, longtime U.S. Army officer W. W. Loring, and the most promising of the lot, ex-West Point tactics instructor Robert S. Garnett. Garnett was soon dead supervising his small force in a river crossing, the war’s first general of either side to die in action.

On September 10, Union General William S. Rosecrans defeated Confederates under Floyd at Carnifex Ferry–partly because Wise refused to reinforce Floyd, whom he despised. The following day, Lee initiated a seven-day campaign around Cheat Mountain. He evolved a complicated plan requiring his force to split into five detachments and attack a force atop the mountain in a driving rain. The officer whose weapons were to initiate the battle, unnerved by the sound of enemy drums, refused to fire.

Lee eventually ordered another column to attack, but the disjointed movements failed. He had to retreat. The withdrawal, along with the Floyd disaster, cost the Confederacy much of western Virginia. Lee’s supposed timidity had gained him an early derisive nickname his detractors would soon come to regret had ever passed their lips:

“Granny.”

(For more information see The New York Times Complete Civil War by Harold Holzer and Craig L. Symonds, eds., Black Dog and Leventhal Publishers 2010; With Malice Toward None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln by Stephen B. Oates, Harper & Row 1977; Lincoln by David Herbert Donald, Simon & Schuster 1995; The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War by David J. Eicher, Simon & Schuster 2001; Grant by Jean Edward Smith, Simon & Schuster 2001; Lee by Clifford Dowdey, Little-Brown 1965; The Civil War Almanac by John S. Bowman, exec. ed., Bison Books 1982; Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War by Patricia L. Faust, ed., Harper & Row 1986; and Generals in Gray and Generals in Blue by Ezra J. Warner, LSU Press 1959 and 1964.)

1961

As September opened, the quiet loner Robert Moses was becoming high-profile in Mississippi. By month’s end, he would be legendary–and widely regarded by blacks and whites as a dead man walking.

Moses had been the first SNCC member to push for a voter registration campaign in the Deep South, but he was not its originator. The idea had come from a courageous black service station owner named Amzie Moore in Cleveland, Miss. Moses had met Moore on a July 1960 foray seeking volunteers for SNCC, and Moore had given him a place to stay. During this visit, Moore had urged Moses to bring Freedom Rider-style students into Mississippi to seek black voting rights instead of to desegregate transportation facilities.

Moses returned a year later to do just that. By September 1961, he and two teenaged helpers were amid the campaign. During this month they would see blacks arrested and charged with disturbing the peace for demanding rights ranging from the vote to use of a county library and a bus station lunch counter. Whites who beat and otherwise abused them would do so with impunity. The eruptions of increasingly bloody violence seemed headed toward murder.

It had started, of course, with Moses’ quiet fearlessness back in August. His initial attempt to register black voters in the ironically named town of Liberty had brought his arrest. Jailed in Pike County in comparatively urban McComb, population 12,000, he requested and received the customary single telephone call. He made it to a number that SNCC leaders had given him. It was the private number of a Justice Department attorney in Washington.

Top-ranking assistant John Doar accepted the collect call. While jailers listened, Moses told Doar what had happened in Amite County: the registrar had refused to register a small Moses-escorted party of blacks, meanwhile intimidating them with lounging sheriff’s deputies and a Mississippi highway patrolman. Driving back to McComb, he–Moses–had been arrested on a charge of interfering with law enforcement’s performance of its duties.

Doubtless influenced by the call to Doar, a justice of the peace offered to suspend Moses’ $50 fine and release him if he paid court costs of $5. Moses refused. That would be validating an unconstitutional arrest, he said. He remained in jail until, two days later, an NAACP attorney arrived from Jackson to unhappily pay the fine. The staid NAACP, preferring to bring court actions rather than get in the faces of racists in the street, resented having to pay SNCC’s bills. Its representative was even less happy when Moses did not wax especially grateful.

By now, Moses had lit a firestorm. SNCC leaders from Jackson, Nashville, Georgia, and other places gathered in McComb. Moses, though, headed back to Amite County. On August 29 he made a second registration attempt in Liberty. This time he was beaten by the son-in-law of state legislator E. H. Hurst, while Hurst’s son and the son of the sheriff looked on. Despite a concussion that left him bleeding profusely, Moses had insisted on completing his trip to the courthouse–where the registrar hastily closed his office and departed.

Moses’s condition worsened. He was driven to a friendly home outside Liberty belonging to black farmer E. W. Steptoe, across the road from that of state representative Hurst. Moses needed medical treatment, it was decided, and Amite County had no black doctor. Moses had to be taken on to McComb.

There, the gathering SNCC leaders had not been idle. Charles Sherrod (whose wife, Shirley, would be fired from the U.S. Department of Agriculture a half-century later, then exonerated, after being fraudulently charged with racism against whites) began teaching nonviolence to McComb high school students. Marion Barry urged the youngsters to demonstrate at the public library, which refused to serve blacks.

Two of Moses’s young McComb volunteer helpers–too young to vote themselves–were arrested for breaching the peace in the library demonstration and associated lunch-counter sit-ins. The redoubtable Jim Bevel, not long out of Parchman Penitentiary from his own incarceration for Freedom Riding, came down from Jackson.

To a crowd of some two hundred of McComb’s black populace, Bevel preached one of his wild and brilliant sermons. In stark contrast, New Yorker Moses–who spoke, too–could barely be heard. But Moses, like the native Mississippian Bevel, said Mississippi blacks had to keep going. He added that he himself was returning to Liberty the next day. It was for the same reason that Nashville civil rights workers Diane Nash and John Lewis had insisted that violence not be allowed to stop the first Freedom Rides in May.

“We felt it was extremely important that we try and go back to town immediately, so the people in the county wouldn’t feel that we had been frightened off by the beating,” Moses said later.

While Moses and a Freedom Rider named Travis Britt went to Liberty, some black McComb teenagers conducted more sit-ins. Sixteen-year-old Brenda Travis was arrested and thrown into jail alongside adult lawbreakers–to the horror of blacks, who blamed the establishment, and whites, who held SNCC’s “troublemakers” responsible.

At Liberty, Moses angered whites and thunderstruck blacks by swearing out a warrant against his attacker of the previous day, Billy Jack Caston. The county prosecutor consented to argue Moses’s case to a jury, but he warned that a black man bringing such a charge against a white one could be tantamount to suicide. He advised Moses to sleep on it and come back the next day, August 31.

Moses returned the next day and did not back down. Amite County impaneled a six-man jury and called in Caston. By the time the trial began, the crowd of whites had overflowed the courthouse onto the lawn. During the proceedings, shotgun blasts went off outside. The sheriff quickly sent Moses and his party under police escort to the county line. The next day’s newspaper announced that Caston had been acquitted.

Brenda Travis’s trial occurred in McComb the same day as Caston’s in Liberty. Sentenced to thirty days, she could not make bail.

September’s onset only increased tensions. On the 5th, Travis Britt was beaten outside the Amite County courthouse as four blacks tried unsuccessfully to register inside. On the 7th, another Freedom Rider–Nashvillian John Hardy–was pistol whipped in nearby Tylertown by the Walthall County registrar inside the registrar’s office. Hardy was then arrested for disturbing the peace.

The Hardy trial, scheduled for September 22, didn’t occur, though. The U. S. Justice Department blocked it, contravening Mississippi’s state laws and taking the word of black witnesses over that of elected white politicians. The case went before a Mississippi federal judge who called blacks “baboons.” But a federal court of appeals quickly reversed him, its two Republicans voting against the Kennedy-appointed Democrat.

Justice Department attorneys visited Liberty, Tylertown, and McComb and felt the pervading air of imminent danger. John Doar even flew down, meeting Moses for the first time and visiting E. W. Steptoe’s farm.

Steptoe told Doar that he and two other local men were in mortal danger from his across-the-road neighbor, State Representative Hurst, and the related Caston family. Moses had been seen riding in the car of one of the other men, a farmer named Herbert Lee. Lee also had arrived late for one of Moses’ registration classes one evening and had been seen by whites who were taking down license numbers of cars parked outside.

Doar wanted to talk to Lee, but Lee was not at home. Doar had to leave that night to return to Washington. The next morning, he arrived at his desk to find a note from Moses indicating why Lee had been unavailable the previous afternoon.

Moses had gotten a call from the doctor who had stitched his head after his Caston beating. The physician said he was at that moment in a McComb funeral home attending a corpse from Amite County that no one would touch, let alone identify. It had lain for hours outside a Liberty cotton gin before local law enforcement telephoned the McComb funeral home to pick it up.

Moses went to the funeral home. The body was Herbert Lee’s. It had a bullet hole in the head.

(For more information see Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-63 by Taylor Branch, Simon & Schuster 1988; The Children by David Halberstam, Random House 1998; The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader by Clayborne Carson, David J. Garrow, Gerald Gill, Vincent Harding, and Darlene Clark Hine, eds., Penguin 1987; The Struggle for Black Equality 1954-1980 by Harvard Sitkoff, Hill and Wang 1981; and In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s by Clayborne Carson, Harvard University Press 1981.)

###

This is a fantastic idea, and I really enjoyed this entry. Thanks, Mr. Hurst!